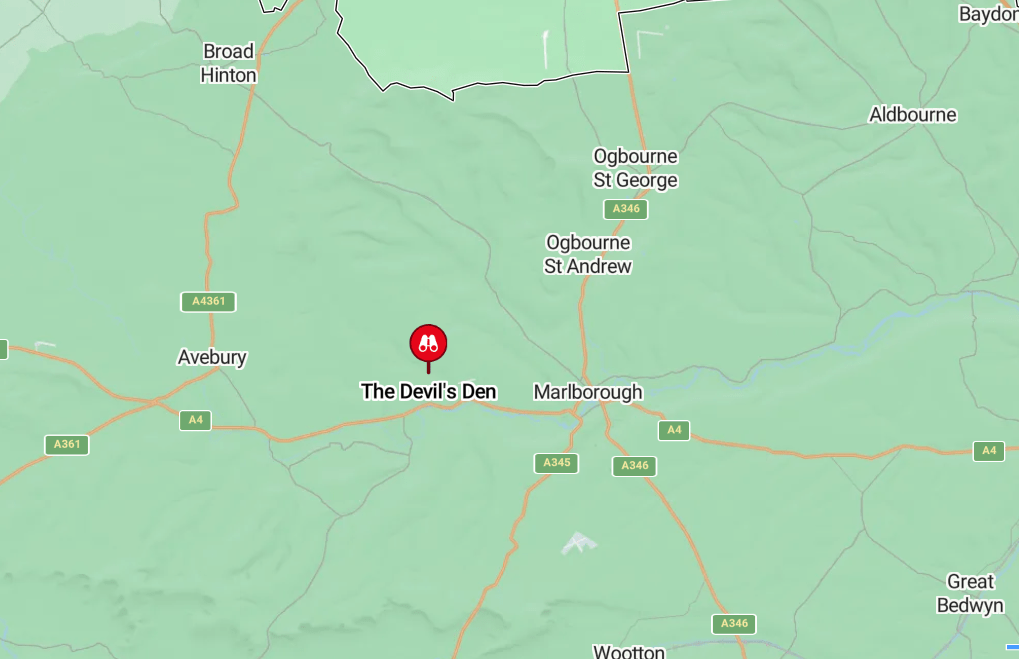

We recently took a trip to Wiltshire, England to see some prehistoric sites. First stop was The Devil’s Den, a neolithic structure in Clatford Bottom. Some refer to this structure as a Dolmen which never had a covering mound, others believe this is the remains of a long barrow…

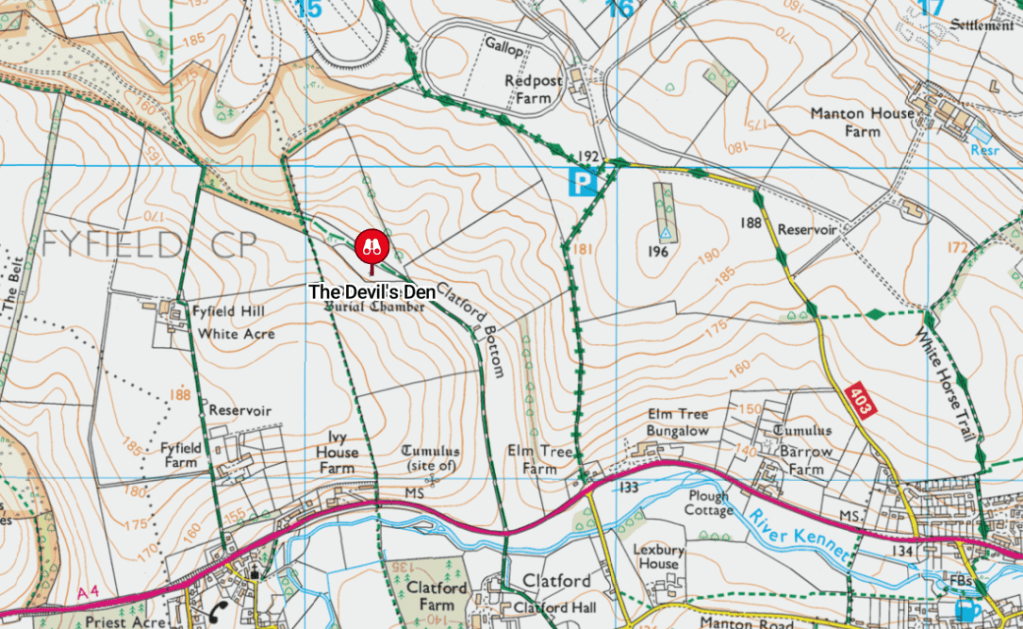

We parked at the “Up On The Downs” carpark and followed the public footpath towards the dolmen…

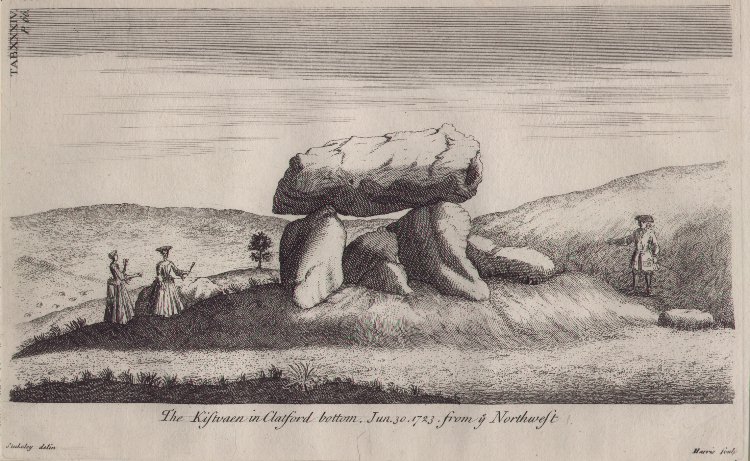

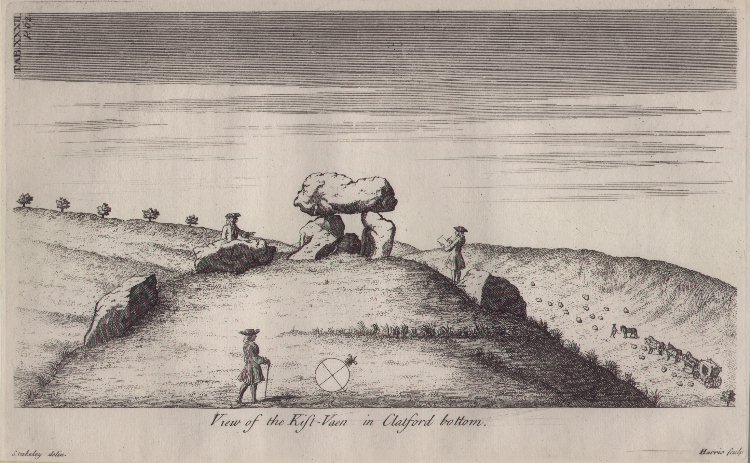

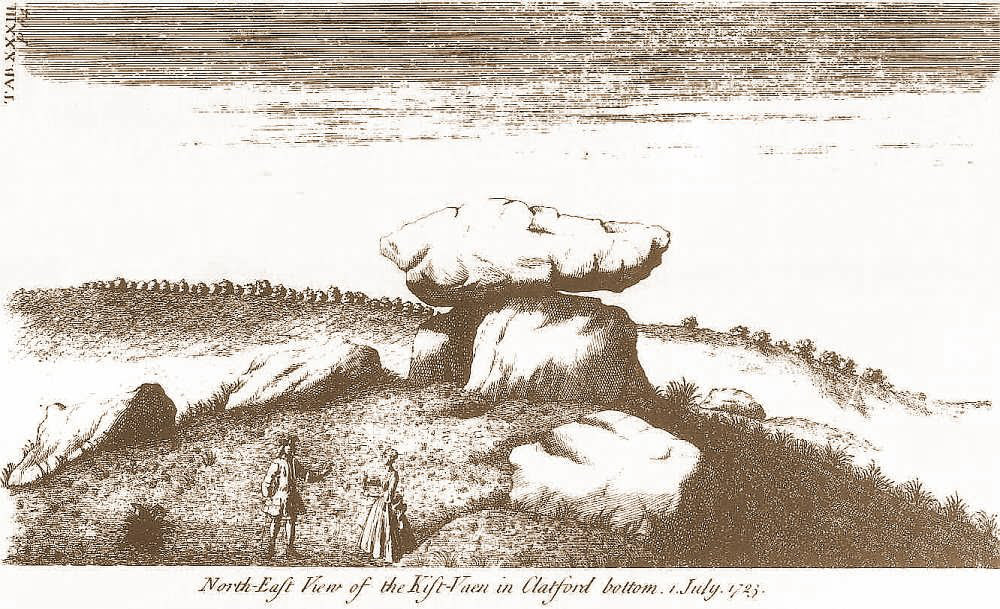

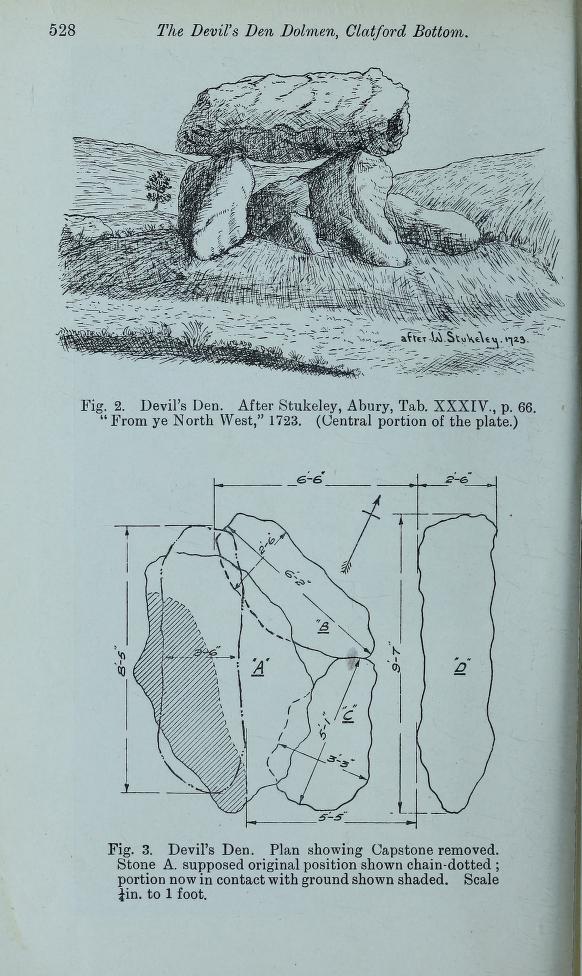

Here are some illustrations of the site provided by William Stukely in 1723 which show what many believe to be a long barrow with several large stones which are no longer in sight. He refers to it as “Kist-vaen in Clatford Bottom”.

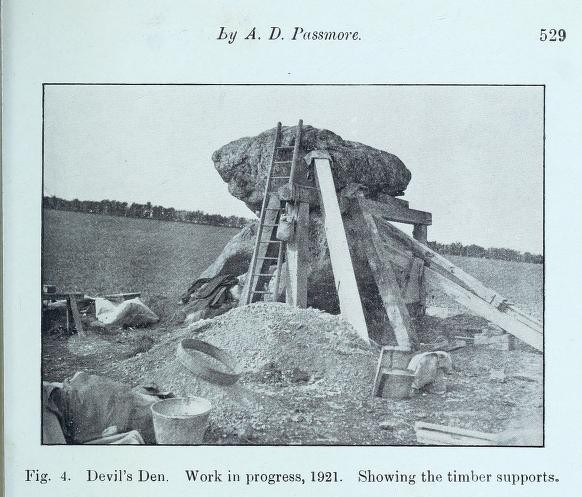

In 1921, Arthur Dennis Passmore led excavations at the site and concrete was then added around the base of one of the upright stones, in an attempt to keep the monument standing. Mr Passmore described the remains of a barrow 230 feet (70 meters) in length. He estimated the capstone to weigh around 17 tonnes. There are also cupmarks on the capstone.

The following is from ‘Guide to the British and Roman Antiquities of the North Wiltshire Downs’ by Reverend A. C. Smith, M.A – 1884:

“This is a noble specimen of the Kistvaen: it stands erect in its original position, only denuded of the mound of earth which, I venture to say (on the authority of the Rev. W.C. Lukis and others best acquainted with these remains) at one time invariably covered them: and this massive erection of ponderous stones is known as the ‘Devil’s Den’, and offers an exceedingly fine specimen of the kistvaen to those who have not made the acquaintance of these ancient sepulchers in other counties. It is not only perfect in condition, but of very grand dimensions; moreover, it is well known to everybody who takes the slightest interest in Wiltshire antiquities.

There are various traditions connected with it. I was told some years since, by an old man hoeing turnips near, that if anybody mounted the top of it, he might shake it in one particular part. I do not know whether this is the case or not, though it is not unusual where the capstone is upheld by only three supporters. But another laborer whom I once interrogated informed me that nobody could ever pull off the capstone ; that many had tried to do so without success ; and that on one occasion twelve white oxen were provided with new harness, and set to pull it off, but the harness all fell to pieces immediately! As my informant evidently thought very seriously of this, and considered it the work of enchantment, I found it was not a matter for trifling to his honest but superstitious mind ; and he remained perfectly unconvinced by all the arguments with which I tried to shake his credulity.

Stukeley says very little of this kistvaen, though he gives several plates of it, his only remark being: “An eminent work of this sort in Clatford Bottom, between Abury and Marlborough.” Sir R. Hoare (in Ancient Wiltshire, North) is more enthusiastic, he says: “From Marlborough I proceed along the turnpike road as far as the Swan public house in the parish of Clatford, and then diverge into the fields on the right, where, in a retired valley amongst the hills, is a most beautiful and well-preserved kistvaen, vulgarly call’d the ‘Devil’s Den.’ It has been erroneously described as a cromlech. From the elevated ground on which this stone monument is placed, it is evident that it was intended as a part annexed to the sepulchral mound, and erected probably at the east end of it, according to the usual custom of primitive times.” – https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015023917472&seq=241&q1=devil

Excavation & Restoration:

From The Antiquaries Journal 1921 –

“The Devils Den – The Rev. E. Goddard, Local Secretary for Wiltshire, sends the following report:

Owing partly to the continual ploughing away and leveling of the ground immediately surrounding it, this well known dolmen, showed signs of probable collapse. The Wiltshire Archaeological Society having sought the advice of the Chief Inspector of Ancient Monuments in the matter, an expert from the Office of Works met representatives of the Society and a local contractor on the spot, and gave detailed instructions for the concreting of the base of the main supporting stone which threatened to give way. This involved the shoring up of the structure whilst the necessary excavations were made, and the work now completed has proved more expensive that had been expected. To pay for this (£54) the Wiltshire Society is now raising a special fund. The excavations were carefully watched and examined on behalf of the Society by Mr. A. D. Passmore, but nothing whatever was found. The ground has been long under the plough, but indications of the long barrow of which the dolmen originally formed a part are still to be seen.” – https://archive.org/details/antiquariesjourn02sociuoft/page/60/mode/1up?q=devils+den&view=theater

Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine:

1922 – “Devil’s Den – The work of concreting the N.E. upright, which was in a dangerous condition, was carried out last September, under the superintendence of Mr. A. D. Passmore, at a cost of £55 raised by subscription. A full account of the work, with list of subscriptions etc appears in the Magazine for June 1922.”

“Tuesday August 1st 1922: …Mr A. D. Passmore followed with an address on “Recent work at the Devil’s Den, and Archaeological Discoveries in the Avebury District”, illustrated with a large series of excellent slides showing the progress of the work at the Devil’s Den..

..As regards to the Devils Den Mr P. Williams asked whether the Dolmen stood on the original surface or on a raised artificial mound. Mr Passmore replied that it stood some 3ft above the original chalk on soil of a different colour and nature from that outside the limits of the barrow, and that he was persuaded this was made ground. On the other hand Mr Cunnington suggested that perhaps this was really a portion of the original surface of the valley above the chalk which had been scarped and retained as the nucleus of the barrow, all the similar soil (such as is often found in the bottom of a valley) having been peeled off (as on a larger scale happened at Silbury) and piled up to form the barrow. As to many of the lines of sarsens on the Downs, Mr Passmore thought that they probably dated from Romano British times and were formed by the stones being cleared off the cultivated fields and dragged to the side to be out of the way of the plough. Mr Goddard remarked that precisely the same thing was being done continually to day on arable land of the chalk.” – https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/132644#page/66/mode/1up

Here is the link to the full excavation report – https://archive.org/details/wiltshirearchaeo411920192/page/522/mode/2up?view=theater

Full excavation report with images:

“On the N. side of the Kennet Valley opposite to Clatford a small valley (Clatford Bottom) runs to the NW. At the mouth of this valley and south of the river, formerly stood the curious circle formed of eight huge and roughly hewn stones seen by Aubery and Stukely, the sketch made by the former being reproduced by Long. 920 yards North of the river and in the abovementioned valley stands the dolmen known as The Devil’s Den. Nearly due North of this and 2100 yards distant stands another dolmen of the same class on the east end of a long barrow, at Dog Hill, Manton ; while in almost the same line to the North formerly stood the Temple Bottom Dolmen at a distance of 1210 yards. Thus, in a N. and S. line under two and a half miles long, four important megalithic monuments once existed.

The Devil’s Den stands just below 500ft contour and almost on the lowest ground in the immediate neighbourhood, being overlooked by high ground within a few yards on either side (NE and SW). An observer standing to the SE and looking NW plainly sees the remains of a large long barrow, much spread and lowered by repeated ploughing (it was under grass in 1863, the turf all round for 30ft being of a different character from that further away) 230ft long and 130ft broad. These measurements can be relied on roughly as regards length but not as to breadth, the whole mound having spread downhill, making an exact breadth measurement impossible except by excavation.

The long axis of the barrow points to the SE ; the end in that direction being broader and higher than the opposite extremity. Roughly about 70ft inwards from the larger end, and not in the present medial line of the barrow stands the Dolmen. Judging by the ground as it remains today, the barrow seems to have had a bayed entrance shaped like the top of the ace of hearts on a card, as is usual with the chambered barrows of Gloucestershire, and as it seems likely was the case with the mutilated long barrow at Beckhampton. The largest ends of the stone face the SE, and this aspect of the dolmen is more symmetrical than the other, proving that the entrance was at this end. It is curiously like Uley, but on a larger scale.

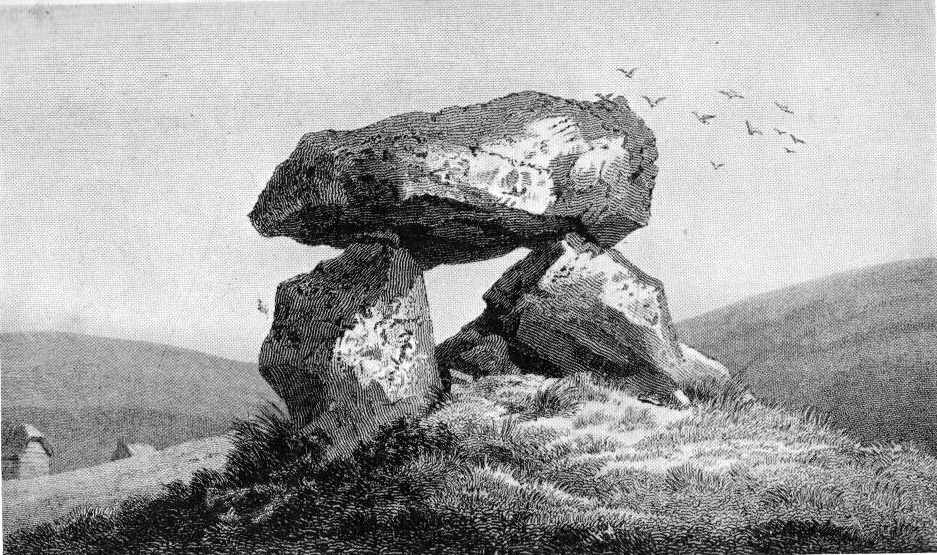

The Dolmen itself, unlike most examples, which are placed on the old ground level, stands four feet above the old surface, and consists on five stones, the NE and SW uprights, the huge capstone (which I estimate as weighing 17 tonnes), and two other stones lying inside the chamber which probably closed the NW end. Beyond these Stukely shows five others lying down, three of which, two on the SE and one on the NE, stood outside the entrance and may be the remains of an entrance passage or the stone lining of a horned entrance. Of the others was one close to the SW upright and the remaining one some yards to the NW. There were thus ten stones in all in July 1723. Although the modern archaeologist cannot accept the fanciful imaginings of Stukely, we are grateful for the general accuracy of his plates, which as regards the monument under discussion are as detailed and correct as a photograph. His plate XXXIV (Avebury Described) shows the capstone as level and the uprights vertical. A comparison of this plate and that of Sir Richard Colt Hoare (Ancient Wilts, vol II) proves that between 1723 and 1810 the base of the SW support slipped outwards and the top of the stone consequently fell inwards, and the whole structure would have collapsed but for the stones lying inside. That to the SE took all the weight and being supported from side slip by a small stone no bigger than a football, which became wedged between it and the NE upright, doubtless saved the monument. The capstone in falling about one foot slipped to the SE. This end of the stone is double the weight of the other, and consequently the double pressure at this end slewed round the SW support considerably out of the parallel, and the flat top of this stone, once in contact with the capstone, is now exposed in the chamber. The partial fall of the SW upright threw a great strain on the opposite one (NE), which was taking the whole pressure on the tip of the stone, the actual contact being only four inches long and one wide at a point near the SE end. This unequal strain has developed a huge crack obliquely through more than half the stone, which may be plainly seen from both sides. The work of destruction thus started, probably with deliberate intent (Smith mentions a tradition of its being pulled at by a team of white oxen), was further helped by some one driving an iron wedge into the crack. (This has now been removed).

Atmospheric denudation had carried all the earth away from the base of the NE stone, and in 1919 I called the attention of the committee of the Society to the immediate danger of its collapse. The committee communicated with Mr C. R. Peers, H.M. Chief Inspector of Ancient Monuments, who sent down an expert from the Office of Works to inspect the monument. He recommended that the base of the leaning stone should be securely concreted to prevent any further movement, and subsequently met the Society’s representatives and the contractor, Mr Rendell, on the spot, and gave detailed direction which were carefully carried out. The whole work was constantly watched by the writer on these notes.

A beginning was made on the 12th September, 1921, by excavating a hole 12ft NE of the center of the NE support. This was carried down to a depth of 2ft through made ground. At this depth a large sarsen stone was reached, and as the necessary support for the props had been obtained the excavation was stopped. Small holes 2ft deep were then made at each end of the side stone, and two other shallow holes were dug to the east to take timbers supporting the capstone. The whole of the timber work and the capstone having been tightly wedged, excavation was begun at the SE end. At the depth of a few inches the base of the stones was exposed, and the cutting was carried down to the depth of 4ft, when signs of the old chalk level were reached, and sufficient depth having been obtained for the concrete bed, work was stopped. This excavation was then filled with concrete (from the Lockeridge pits), and work commenced on the NW end. Here a similar hole was made and filled ; after which the center part was dug out to the same depth and similarly filled, with iron bars bedded in the mass to bind the various sections together. The whole excavation was 9ft long 3ft 6in wide, and 4ft deep, and passed through made ground, but no signs of the old turf level were observed. Every artificial nature was seen, neither pottery, bone, nor flint. Above the bottom of the excavation, which was considered to be undisturbed chalk, was a 4in layer of rubble, then 6in of sand, showing well marked lines caused by having been subjected to water action (probably heavy rain), then 4in of fine grit, the remaining soil above consisting of a peculiar mass of chalky lumps, which broke like marble, interspersed with sand and grit different in character from the soil in the immediate neighborhood, but agreeing with that of the hill side to the north. Much of the base of this hill has been cut away, and I have no doubt that the materials for the formation of this very large barrow were obtained therefrom. Throughout the hole excavation the separate layers sloping outward and downward could be plainly seen.

The concrete bed was then, by means of a frame, carried up 1 ½ ft higher above the previous ground level to take the weight of the stone which overhangs on this side, and was finished off to a surface slanting outward. Under the SE end were deposited two coins dated 1920 and 1921, and at the N end a tile engraved with an account of the work, covered in wax and wrapped in lead was buried. On the top of the concrete was carved in large figures the date “1921”.

The base of the NE upright was of a round section and was merely resting on the ground. A small horizontal test hole was made, passing under the base. As mentioned above, the capstone has apparently slipped slightly to the SE, and it has become the fashion to climb up and to apply pressure at one spot and rock it. This highly dangerous proceeding has now been made impossible by cementing in a sarsen wedge on the SE end of the top edge of the NE support. This cannot be seen unless specially looked for.

A critical examination of the underside of the capstone reveals certain marks which at first appear to be due to pounding with a maul. It is now, however, clear that they are due to weathering.

To ascertain the character of the surrounding top soils trail holes were dug to the E and SW of the dolmen, well clear of the barrow. The sections there seen were different from that of the mound.

I am greatly indebted to Captain Edwards and Mr Taylor, of Manton, for much kindness and advice. Also to Mr M Jones, for the scale plan of the monument. The block illustrating the Devil’s Den, before the underpinning, is kindly lent by the editor of The Observer.”

Here is the video we made covering The Devil’s Den:

Leave a comment