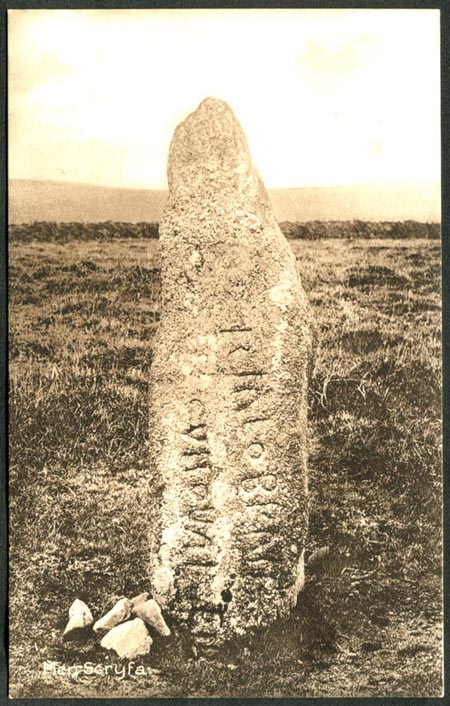

Mên Scryfa, meaning written, or inscribed stone in Cornish. This 1.8m tall stone was likely erected during the Bronze Age, but contains an inscription from the 5th or 6th century AD. This reads RIALOBRANI CVNOVALI FILI, a Latinised form of Cornish meaning ‘Royal Raven, Son of the famous leader’. Its said that a battle was fought nearby, and that Riolbranus was slain and buried at the spot, with the stone being the exact height of the warrior.

Antiquarian William Borlase described the stone in 1769 as lying on the ground. It was re-erected in 1824 at the same time as Lanyon Quoit was restructured by Captain Giddy of Logan Rock infamy. By 1849 it was reported in a local magazine as lying down again. In 1862 the Cambrian Archaeological Association visited and records the stone as having been re-erected again, although it was noted that ‘had not the Cambrians proposed to visit… this celebrated stone would have remained for a long time to come, in its fallen state, or it might have been taken away, like some others of the kind, and used for a gate-post.’ The last word of the inscription is now buried beneath the ground.

Men Scryfa was vandalised in June 2023 when the top of the stone was covered in petrol and set alight, burning lichen on the tip. Earth around the base of the stone had also been dug up, raising concerns that the stone was intended to be toppled, according to BBC News – https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-cornwall-65811471

The stone is a short walk from the iconic Men-an-Tol. Situated just off The Tinner’s Way, an ancient 18 mile trackway which passes many historic (and pre-historic) sites in the Penwith landscape. The Tinner’s Way was also important in the 18th and 19th century during the mining boom, when supplies would have been transported using the track.

John Thomas Blight visits the stone and described it in ‘A week at the Land’s End’, published in 1861:

“The Men-Scryfa, “written stone”, is now within half a mile. As an ancient inscribed monument, it is one of the most important in the kingdom. The inscription is, “Rialobran-Cunoval Fil” ; at length, “Rialobranus Cunovali Filius”, signifyying that Rialobran the son of Cunoval, was buried here.

It has never been ascertained who this Rialobran was. Rioval, a British leader who lived in the year 454, and Rivallo (alias Rywathon) brother of Harold, the son of Earl Godwin, have been hinted at. The question is not now likely to be settled ; and in a few years, most probably, the stone itself will be numbered amongst the things that were. A clown of the neighbourhood, possessed with a longing desire to become suddenly rich, had heard that crocks of gold were occasionally found buried beneath great stones ; the thought haunted him day and night ; and no peace had he until he relieved his mind by digging a deep pit around the Men-Scryfa, and causing it to fall, face downward, in which disgraceful position it has ever since remained.

The inscription was written before the alphabet was corrupted, i.e. before the letters were joined together by unnatural links, and the down strokes of one made to serve for two ; which corruptions crept into the Roman alphabet, used by the Cornish Britons, and increased more and more until the Saxon letters came into use, about the time of Athelstan’s conquest. The most observable deviation from the Roman orthography in this monument is, that the cross stroke of the Roman N is not diagonal as it should be, nor yet quite horizontal as used in the sixth century ; it is therefore probable that this inscription was made before the middle of the sixth century. though some have considered it a heathen monument, Dr. Borlase thought it Christian, and erected before it became unusual to place the cross before the name.

A popular tradition is, that a great battle was fought near the spot ; that one of the chiefs or leaders was slain and buried here ; that this inscribed granite pillar was erected to mark the place of burial ; and that its length, about nine feet, was the exact height of the warrior.” – https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_iOUGAAAAQAAJ/page/n44/mode/1up

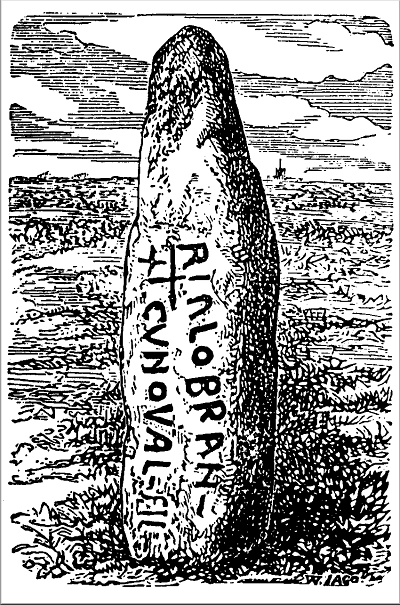

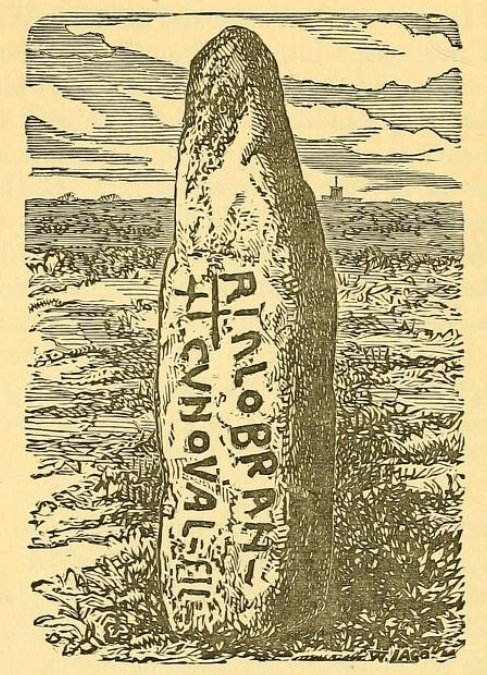

The following is from the Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall, 1864 (including illustration):

“This venerable relic was inspected during the Autumn Excursion. Its title almost claims for it pre-eminence as THE Inscribed Stone of Cornwall ; even the land about it seems to have been named from it in the Cornish language, another proof of its ancient character.

Many generations have regarded it with interest ;and the present proprietor, with the best intentions, but with misdirected zeal, prepared it specially for the visit of the Members and Friends of the Royal Institution of Cornwall, by coloring its letters blue!-where he could trace them. Fortunately the incisions appear to be uninjured, and some of them had altogether escaped the painter’s observation.

A close examination and rubbing of the stone convinced me that the inscription differs in some points, though not very materially, from the generally received account of it. The F, appeared upside down. In former illustrations of the stone I have seen it given non-inverted, of quite a different shape, and curved over to meet the top of the I. Dr. Borlase has so represented it, and other have followed his example. He has also stated-“Mr. Moyle thinks that Rialobran was a heathen. It is true that there is no cross at the beginning of the Inscription – I rather think it a Christian Monument erected probably before it became usual to place the cross before the name.” Notwithstanding this declaration, we at once percieved on visiting the stone, large crossing lines in the early part of the inscription. Dr. Barnham and Mr. H. M. Whitlet saw them with me. In the rubbing they distinctly appear. They are somewhat peculiarly placed, but have the same appearance of great age which characterizes the letters.

I have sought to ascertain whether the cross-markings could have been added since Dr. Borlase published his interesting account and engraving of the stone in 1754-69. – I find that they must have existed in his time ; for, Martyn published (in his second sized map) 20th April, 1749, in advance of Dr. Borlase, a sketch of the stone displaying these very marks- He also “dotted in” the F, as being of a form he could not quite understand.

Dr. Borlase, then, rightly expected to find a cross at the commencement of the inscription, but overlooked or failed to recognize anything of the kind. Nevertheless, the marks were there, and still remain, not as interpolations, but as having been, apparently, scriven when the letters were.” – https://archive.org/details/journalofroyalin4187173roya/page/69/mode/1up?q=scryfa

From the Cornish Archaeology website, regarding damage to the stone: “In the early 1840s the Cornish press carried several letters listing archaeological monuments in west Cornwall which had recently been damaged or destroyed. The letters, signed ‘P’ and subsequently reprinted in the nationally circulated Gentleman’s Magazine, were by the Reverend Henry Penneck, a leading light in the Penzance society. ‘P’ observed that the

‘spread of our daily inscreasing population into the most secluded districts unveils to public gaze those monuments which were formerly little known and seldom seen, and the demand for stone for the new houses etc everywhere building will shortly consign the remainder, as it has so many already, to the tender mercies of the stone-carrier and the mason. As a singly specimen of this sort of procedure in the now densely-inhabited parish of St Just in Penwith, I may mention that some of the circles described by Mr Buller only two years ago can no longer be found [Buller’s statistical account of the parish of St Just was published in 1842]. they have been used in building cottages etc although in St Just stones are probably more plentiful than blackberries’ (‘P’ 1844, 487-8).

In 1849 the same author reported having found the Men Scryfa inscribed stone (Madron) ‘lying prostrate in the Croft where it had stood, but which having recently been broken up for tillage has been cleared of all but this and a few other blocks too large to admit of their being easily carted away except piecemeal’. (RCG, 5 October 1849, p6)(Fig 11.) He recalled that the stone had previously been re-erected in the 1820s, at the time that the capstone of Lanyon Quoit was replaced.

‘At that period the act of raising it was simply one of laudable reverence, for, whether standing or prostrate, its situation in an out of the way Croft, seemed to promise it a sufficient security from injury. The case, however, is widely different now, when there is such a demand for our granite ; and, as the surface blocks are specially coveted, not only because they are more durable than most of the quarried material, but also because they are cheaper, leave being readily obtained for their removal which renders the land available for tillage, – it is much to be feared that the inscribed stone, no longer distinguished by its upright position, will be treated with as little ceremony as the nameless ones amongst which it lies should no effort be made to preserve it, it seems indeed more than probably that it will shortly pass into the hands of the masons’.

Echoing Carne’s comments two decades earlier, Penneck was concerned that future antiquarians would have to console themselves with the illustration of the Men Scryfa in Borlase’s Antiquities. ‘To that work too they will, at no distant day, be obliged to resort, in order to form a guess what the neighbouring relic, Chun Castle, once was, so rapidly it is disappearing ; for although the hill side is covered with stone, its vile destroyers, if not with deliberate malice, at least with very perverse taste, prefer to pillage its ramparts and even its massive gateway.’…

…The visit to Cornwall in 1862 by the Cambrian Archaeological Association brought further attention to antiquities. The Men Scryfa was again re-erected, although it was noted that ‘had not the Cambrians proposed to visit… this celebrated stone would have remained for a long time to come, in its fallen state, or it might have been taken away, like some others of the kind, and used for a gate-post.’ – https://cornisharchaeology.org.uk/app/uploads/2022/08/Cornish-Archaeology-Vol-59-2020.pdf

The following is quoted from ‘Guide to the Men-an-Tol Holed Stone and other nearby sites’, by Ian Cooke, 1990:

“This stone is a granite pillar commemorating the death in battle nearby of an Iron Age warrior of royal birth. It is about six feet high and has an inscription on its northern face in two vertical lines with the last word now being below ground level.

RIALOBRANI

CUNOVALI FILI

Although the stone itself may have been a much earlier menhir (a long, or standing, stone) the inscription itself dates from the post-Roman Iron Age of the 5th or 6th century AD, and is a Latinised form of the native Celtic language. This was a common fashion of the upper classes who had a superficial knowledge of Roman culture and who wished to be thought of as ‘civilised’.

RIALOBRAN (RYALVRAN)

royal raven

CUNOVAL(CUNO-UALLOS)

famous leader of glorious prince

This signifies that the stone is ‘of the Royal Raven, son of the Glorious Prince’. The raven, a bird of carrion linked with death and the battlefield, was believed to have magical power for those who worshipped it (the raven was one of the forms taken by the Irish Morrigan – goddess of war and death) and the bird was venerated over much of northern Europe, being an important symbol in an aggressive warrior society. Celtic legends link the name of Bran to a warrior king of ancient Britain, keeper of the cauldron of immortality, whose decapitated head continued to have powers of speech and was later to be buried on the site of the present Tower of London where ravens are kept on the premises – should they ever leave, then tradition warns that the Tower will fall and the kingdom with it. Bran appears in Arthurian legend in a variety of differing names and it seems that he was a Celtic solar war god – the Brennus who led the armies that laid waste to Roman and Greek cities. Obviously a name taken by mortals to instill terror and confusion within an enemy. Ancestry was crucial in establishing the legitimacy of royal leadership and is shown here by the inclusion of the father’s title on the memorial stone.

The story of Ryalvran is very ancient and it seems that an invader attacked the Glorious Prince, seized his lands, and occupied his strategically important hillfort at Lescudjack (Penzance) which protected the harbour area and the tin assembly points around Mount’s Bay. the defeated royalty was forced to flee, possibly to the area around Carn Euny and the hillfort of Caer Bran (Raven Castle). The Royal Raven tried to regain his father’s territory and a great battle was fought on the moors where Men Scryfa now stands. Ryalvran was killed and his body buried by the stone which was said to correspond to the height of the dead warrior. That such a monument could be erected suggests that the battle was won and that his tribal lands were retaken.

The inscription of Men Scryfa is contemporary with the re-occupation and new defensive works carried out at the nearby fortification of Chun Castle. Early in the 19th century a local miner, who had heard that gold was to be found under the stone, dug around it and caused it to fall, nearly losing his life in the process. The stone was re-erected at a deeper level in about 1824 with the same machinery used to replace the capstone of Lanyon Quoit and the famous Logan Rock at Treen.

Alignments: Men Scryfa = Barrow remains to north-west of Nine Maidens at 43243530 = 3 1/2 foot high boundary stone between Zennor and Gulval parishes (this stone has drill arks down one side so if ancient it must have been split from a larger standing stone) = Mulfra Quoit. – https://archive.org/details/guidetomenantolh0000cook/page/7/mode/1up

Leave a comment