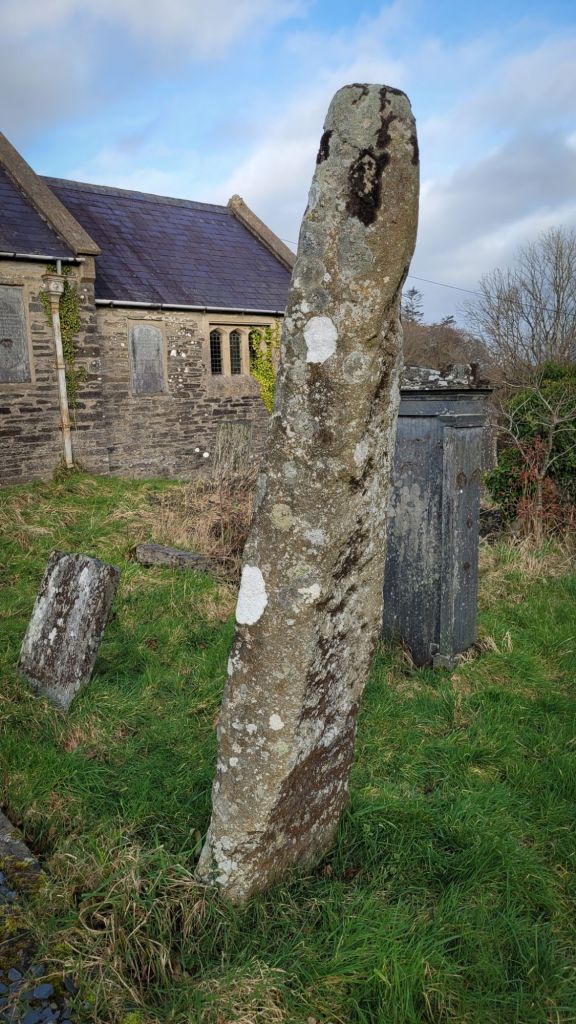

Within this churchyard is a 7ft tall spotted dolerite stone inscribed with 5th century Ogham markings as well as a cross, which was thought to have been added around the 9th or 10th centuries CE. A few people have also suggested there are prehistoric cup marks on one side of the stone.

The Ogham is thought to translate to ‘of Nettasagri son of the kindred of Briaci’. The name is an Irish compound possibly meaning ‘champion of a leader’. In ‘A Corpus of Early Medieval Inscribed Stones and Stone Sculpture in Wales. Volume II. South-West Wales’.. Nancy Edwards discusses how this is the only Ogham monument from Wales using the phase maqi mucoi (‘son of the kindred of’). It is thought that this inscription would suggest the stone was commemorative in function, perhaps by the elite and followers of Irish descent (Deisi) who may have settled in North Pembrokeshire.

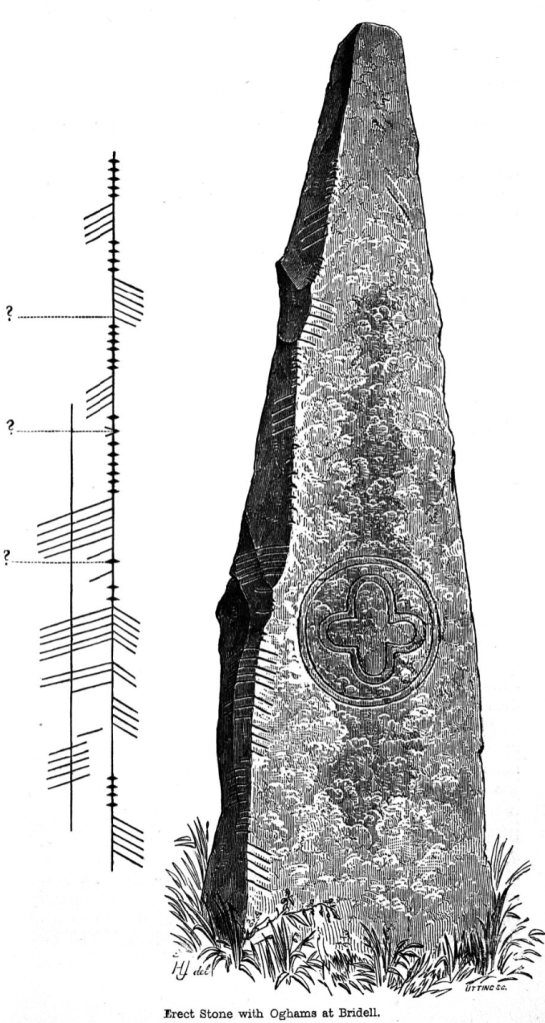

The earliest record of the stone we could find is from 1860 in the Archaeologia Cambrensis, ‘Early Inscribed Stones of Wales – Erect Stone With Oghams at Bridell’ by H. Longueville Jones. In this article the stone is noted as possibly being the “longest collection of Oghams on any stone in Wales”.. He also provides the above illustration:

“At Bridell, in northern Pembrokeshire, near Cardigan, there is standing erect in the church-yard, to the south of the sacred edifice, and partly shaded by a venerable yew tree, a stone, commemorating some Christian man probably interred beneath it. It is from the porphyritic greenstone formation of the Preseleu Hills, such as those at St. Dogmael’s, Cilgerran, and elsewhere used for similar purposes ; but it is somewhat more elegant in shape, tapering uniformly to the top, nearly covered with a thin grey lichen, and hardly, if at all, injured by the weathering of many centuries.

On its northern face is incised an equal-armed cross within a circle, early in its character, as much so perhaps as any cross to be met with in this district. There are no other sculptures, nor letters, upon the stone ; but all along the north-eastern edge, and down part of the eastern side, occurs a series of Oghams, which may be considered almost uninjured. This state of good preservation may be inferred first of all from the very precise manner in which the incisions have been made, and next from the circumstance of their following the original indentations and irregularities of the edge, thus showing that the stone was in form just as we now see it when these occult characters were first cut upon it.

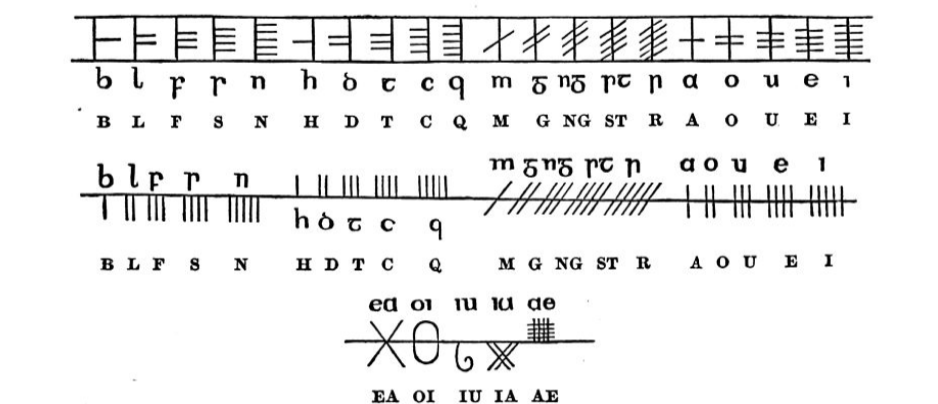

An illustration, reduced from several accurate drawings and rubbings, from sketches, from repeated handlings, and from minute examinations made during several successive years, is here annexed ; but, though it is hoped that due fidelity of delineation has been attained, it is much to be wished that a careful cast of this stone should be taken, and that copies of it should be submitted to the inspection of Irish antiquaries, if needed they still feel disinclined to come and see for themselves these ancient stone records of the sister isle. We dwell on this circumstance because there are many peculiarities to be observed in the Oghams on this stone ; and because, even with the aid of Professor Grave’s alphabet, which we here again append, this inscription has not been hitherto satisfactorily deciphered. A single cut occurs on the face of the stone near the upper portion ; and it will be understood that the Oghamic marks are made darker than they actually are in order to catch the eye more decidedly.

This is the longest collection of Oghams on any stone in Wales, and it extends partly over three lines, if our interpretation of it is correct. A scheme of it, which we offer with diffidence, is given ; and we recommend member to try and read it by the aid of the alphabet just mentioned- and alphabet verified, as they are aware, by the SAGRANVS stone in the neighbouring precincts of St. Dogmael’s Abbey. Whether all the Oghamic marks on this stone are to be considered as forming only one line, or whether they are to be divided into two or three, difficulties seem to present themselves. The two opening and the two closing Oghams on the edge are very decided in their character, so are the longer cuttings which extend across the east side of the stone ; but though we think that we can approximate to a reading of some satisfactory nature for ourselves, we prefer not bringing it forward until after further conference with antiquaries experiences in such matters.

The church, which is under the invocation of St David, is a chapel belonging to Manor Deifi, beyond Cilgerran. Ot contains a font of the thirteenth century, similar in design to most Pembrokeshire fonts, viz. A cubical block, chamfered off, and cut into curcular sides beneath ; but the edifice itself is not older that the fifteenth century, when it probably replaced an older building. **Note that the church was entirely rebuilt in the 1880s**

In a field adjoining the church-yard to the west, there were discovered some years ago a considerable number of interments each in a kind of cistfaen ; and this would indicate that the precincts of the yard extended much further than is now the case.- H. Longueville Jones” – https://journals.library.wales/view/2919943/2994777/64#?xywh=-2685%2C-201%2C7549%2C3931

We then have a long and interesting response to H. Longueville Jones’ account, published in 1872 by Richard Rolt Brash, M.R.I.A, which reads:

“..Mr. Jones gives, with his illustrations, a scheme of what he believed the characters on the stone to be, in relation to its angular formations ; but if we refer to his pictoral engraving, which has all the appearances of truthfulness, it will not bear out the scheme, which also renders the inscription confused and unintelligible. That there are difficulties connected with the inscription is undeniable, arising from two causes, – the prolongation of some of the upper and crossing consonants to an angular projection on the eastern face of the stone giving some countenance to Mr Jones’ idea of a second line of inscription ; and the wearing and partial obliteration of some of the characters on the main angle. Regarding the first, I should say there was no second angle, and no second line of inscription intended. The characters are generally boldly cut, perhaps unusually long, -the prolongation of the consonants being a mere freak of the engraver. Several Irish inscriptions present us with examples of very long scores done in the dashing style of those on the Bridell stone.

The whole of the inscription was evidently intended to refer to the front angle, which runs pretty evenly from bottom to top. If additional sspace had been required, the right hand angle, according to universal usage, would have been selected for its continuance ; in truth, a portion of the former is left uninscribed at the top, shewing that the inscription is complete, with room to spare on the one angle…

..I found that the illustration published in the Arch. Camb. was a good representation of the monument; and the inscription, with a few exceptions, faithfully copied. The first score of the first letter is faint. In the third character there is some trace of a sixth score, which I believe to be but a fray in the stone. My copy agrees with Mr. Jones’s in the first nine letters. To the tenth he gives the value of H. It is true that the part of this score below the line is worn, and almost indiscernible; put taking the five previous letters into combination, it ls quite evident that the whole formed the proper name, sagrom. The eleventh, to which he also gives the value H, is undeniably an M, the score crossing the line or angle. This, with the three following letters, form the word maqi. The fifteenth character is an M, the lower half of which is defaced. That such is its value there can be no doubt, as the following four letters, with it, form a word so remarkable, and so often found in these inscriptions, the word mucoi. The last four letters are quite perfect and legible.

The whole reads as follows : NEQASAGROM MAQI MUCOI NECI. Neqasagrom the son of Mucoi Neci.

The name of the individual commemorated is Sagrom, with the prefix Nee or Necua. What confirms the identification of this name is the fact that we have it on another Ogham inscribed stone in the same district. The bilingual monument at Llanfechan gives us Sa- gramni, i. e., the genitive form of Sag ram. The Gaed- helic scribes were not particular in the use of vowels. Again, we find this name on the back of the Fardel Stone, in debased Roman letters, sagranvi. The name must have been a representative one, and must have been borne by eminent chiefs or warriors. To such only could those remarkable monuments have been erected; and it is certainly curious and suggestive to find this name in districts so remote as the seaboard of Cardigan and the shores of Devon. The prefix Nee, Neach, is very frequent in Gaedhelic names, as Nectan, Neachtain. Sagram is of the same type as Segan, Segda, Seghene, Seghonan. The name or designation Mucoi I have already alluded to. The concluding name or patronymic is Neci; which, indeed, is the prefix of the first name.

A similar instance is to be found in the inscription at Llandawke, near Laugharne, Carmarthenshire, where we have the formula barrivendi filivs vendibari. I have thus endeavoured to give a reasonable render¬ ing of this inscription. It is consistent with the formula generally found on monuments of this class, and it takes no liberties with, the original beyond what it discloses in the obvious combinations of its letters. I do not consider that the ornament incised on the face of the stone was intended to represent a cross; neither is it of any remote antiquity. It is palpably a mediaeval quatre- foil, and cannot be older than the thirteenth century. I cannot, therefore, look upon this memorial as commemorating “some Christian man probably interred beneath it” as surmised by Mr. Jones. We have not a scintilla of evidence that this archaic character was ever used for Christian purposes or in Christian times. The inscription is in a character peculiar to the Gaedhil. It is in the language of that people, and its formula is in exact accordance with that found on the great majority of their monuments. It bears no sacred name, no word of Christian hope or benediction. It stands grim, rugged, and solitary, a silent but palpable witness of the existence on Welsh soil of that restless and ubiquitous race.

Mr. Jones states that ” in a field adjoining the church¬ yard, to the west, there was discovered a considerable number of interments, each in a kind of cistvaen; and this would indicate that the precincts of the yard ex¬ tended much farther than is now the case” (ibid.,p. 317). It is here evident that the present graveyard occupies a portion of the site of an ancient pagan cemetery, and will account for the presence of the Ogham pillar. Dr. Ferguson (Pro. R. I. A., vol. xi, p. 48) reads this inscription, NETTASACROHOCOUDOCOEFFECI. This is an erroneous reading. As I have already shewn, the third character is a Q, and not a double t. There is a weather- fray in the stone, which he has mistaken for a score. The Rev. H. L. Jones agrees with me in this character. There is no such combination of letters as hoc, neither oudoc, or effeci. These are most palpable errors, and I fear have been caused by Dr. Ferguson reading from his paper-mould, and not from the stone, as well as by his imagining the inscription to be in Latin forms. His inspiration is quite evident from the following passage: ” If so, the verbation of the Bridell Stone would seemingly run, ‘Netta Sagro hoc or (Sagromoc) Oudoco effeci’. There was an Oudoc, bishop of Llandaff, in the seventh century. If Moc, the reading might be Moci doco, etc.; and Docus, a more eminent personage, be the one intended’ (Ibid.) The letter D does not appear in the entire legend, and therefore Oudoc and doco fall to the ground. The last five letters are ineci in the most legible and palpable forms.

This custom of taking a few letters of a legend, which bear some resemblance to a local historic name, and thence endeavouring to construct a reading, has been a source of much error and confusion. The names found upon Ogham monuments belong to a period too remote to give us any just grounds of identifying them with personages within the range of historic record; while the fact that such proper names were probably as common as are John, Thomas, or William, with us, renders such speculations perfectly hopeless.

The finding of the name or designation Mucoi on this stone completes the identification of the inscribers of the Welsh Ogham pillars with those of Ireland. I have found it on sixteen distinct inscriptions in that country. In some instances it appears to be a proper name, as in an inscription from Drumloghan, co. Waterford, which reads “Deago maqi Mucoi’ i, e., “Deago, the son of Mucoi”; and in one from Ballinrannig, co. Kerry, which reads ” Naficas Maqi Mucoi.” Again, it appears as a designation or title, as in an inscription from Greenhill, co. Cork, which reads ” Dgenu Maqi Mucoi Curitti.” Here the person commemorated is ” Dgenu”; the patronymic “Curritt,”aname also found upon several Ogham inscribed pillars; while the word Mucoi is evidently a designation or title of ” Curritt.” In some cases this title comes after the patronymic, as in an inscription from Kilgravane, co. Waterford, which reads ” Na maqi Lugudecca Mucoi.” I have in another place hazarded some conjectures respecting this word. It is identical with the Mucaidhe of our Gaedhelic dictionaries, which signifies & swineherd; but which does not appear to have been used in the same sense which we attach to it, but rather to have distinguished a person wealthy in herds of this animal, which appears to have formed an important item in the substance of Irish chieftains and farmers in ancient times, Thus we find it occupying a foremost place in the tributes paid to the reigning monarch by the provincial chiefs, as recorded in the Book of Rights as follows : “Ten hundred cows and ten hundred hogs from the Muscraidhe”; “ten hundred cows and ten hundred hogs from Ciarraidhe Luachra”; “two thousand hogs and a thousand cows from the Deise” (p. 43). The Muscraidhe were a tribe which occupied a large district in the county of Cork, now known as the baronies of East and West Muskery. Ciarraidhe Luachra embraced the western districts of the county of Limerick, and a large portion of the north and east of Kerry. The Deise were a tribe located in the present county of Waterford. An examination of the Book of Rights shews that the counties of Cork, Kerry, and Waterford, were the great swine producing countries; and that the kings and chiefs kept enormous herds of them, and had special officers set apart to take charge of them. Thus we are informed, in the above authority, that “Durdru” was the mucaidhe, or swineherd, of the ” King of Ele,” and “Cularan” the swineherd of the ” King of Muscraidhe.”

The term Mucaidhe, or its Ogham equivalent, Mucoi, is analogous to that of Bo-Airech, which we frequently meet with in Irish MSS., and which is included in the orders of nobility; literally signifying one wealthy in cattle, from bo, a cow, and aireach, a term of distinction. That the term Mucaidhe or Mucoi (for the pronunciation is the same) may have become a tribe or family name is not unlikely. We have our Shepherds and Herdsmans, as well as our Foxes, Bulls, Lyons, Hares, Wolfes, and Hogs. Muc is Gaedhelic for boar; and the custom of taking family names from animals was as prevalent in Ireland as in other countries. Thus they have Mac Sionach, i. e., son of the fox; Mac Tire, son of the wolf; Mac Cue, son of the hound, etc. That the boar w&s held in great estimation in Ireland, if not actually reverenced, we have strong indications in the traditions and folk-lore of the peasantry, as well as in the large place it holds in the topographical nomenclature of that island. The porcine terms, muc, tore, lioth, and other words connected with that animal, as chollan, a hog; cro, a stye; baub, a young pig ; will be found entering in to the names of hundreds of localities there. Thus an ancient name of Ireland was Muc-Inis, i. e,, boar-island. It was also named in ancient MSS. Banba. There is a Muc-Inis in Lough Dery, on the Shannon. Also we find the same on the coast of Clare, and on the banks of the river Brick in Kerry. One of the western isles of Scot¬ land is named Much, and the proprietors were named lairds of Muck. We find Muchros in Killarney, Much Moe in Monaghan, Bally-na-Muc, Muckalee, and Kill- na-Muckey, co. of Cork; Cool-na-Muc, co. of Waterford. One of the early kings was named Olmucadha, or ” Of the Great Swine.” He reigned from a.m. 3773-3790. One of St. Patrick’s earliest converts was named Mochoi; and in the forms of Mochai, Mochoe, etc., it is to be found in about thirty instances in the Martyrology of Donegal. Numerous examples occur in the Annals.

The prominence thus given to this animal in our legendary lore and topographical nomenclature suggests the idea that the boar may have been identified with that system of animal worship which we have some reasons for believing once existed in this country. The Hindoos reverence the varaha, or boar, as one of the incarnations of Vishnu; and in the geography of that race, Europe is set forth as “Varaha Dwipa,” or boar- island, equivalent to the Irish Muc-Inis. He (Vishnu) is represented as residing there in the shape of a boar, and he is described as the chief of a numerous offspring of followers in that shape. There are some indications of this cultus in the writings of the Welsh bards, as also in the Druidic songs still preserved among the Bretons.

Upon the whole we may safely determine that this was a personal and tribe-name extensively used in the south and west of Ireland. The fact of sixteen of our existing Ogham monuments bearing it is quite ample evidence ; but corroborated by the numerous examples of its use in existing documents, it is undeniable. I am very certain that many unnoticed Ogham inscriptions still exist in Wales, particularly in the counties of Cardigan, Pembroke, Carmarthen, and Glamorgan, and more especially on the seaboard of these districts. How desirable it would be if local antiquaries would undertake a careful search for such! Richard Bolt Brash, M.B.I.A.” – https://journals.library.wales/view/2919943/3000066/83#?xywh=-1338%2C284%2C4854%2C3226

St David’s Church:

Coflein:

“St David’s Church is situated within a irregularly-shaped (possibly formerly curvilinear) churchyard. A possible curvilinear outer enclosure is visible in the field pattern to the north of the church. An ogam-inscribed (thought to date to the 5th century) and cross-incised (thought to be 9th- to 10th- century) stone, Bridell 1 (NPRN 304080) stands in the churchyard. thought It may be in situ, or may have originally been associated with cist graves reportedly found in the field to the west of the churchyard in the 19th century. The church was a parish church during the post-Conquest period, in the gift of the Welsh community of the Deanery of Emlyn. It is thought to still be in the multiple patronage of the freeholders of the parish.

The church is a Grade II listed building constructed of squared slate rubble. Although the church stands on the foundations of its medieval predecessor it was entirely rebuilt in 1886?1887. It consists of 2-bayed chancel, 2-bayed nave, north porch and north vestry. Its font, with square bowl, circular stem and square base, is thought to be 12th- to early 13th century in date.”

Leave a comment