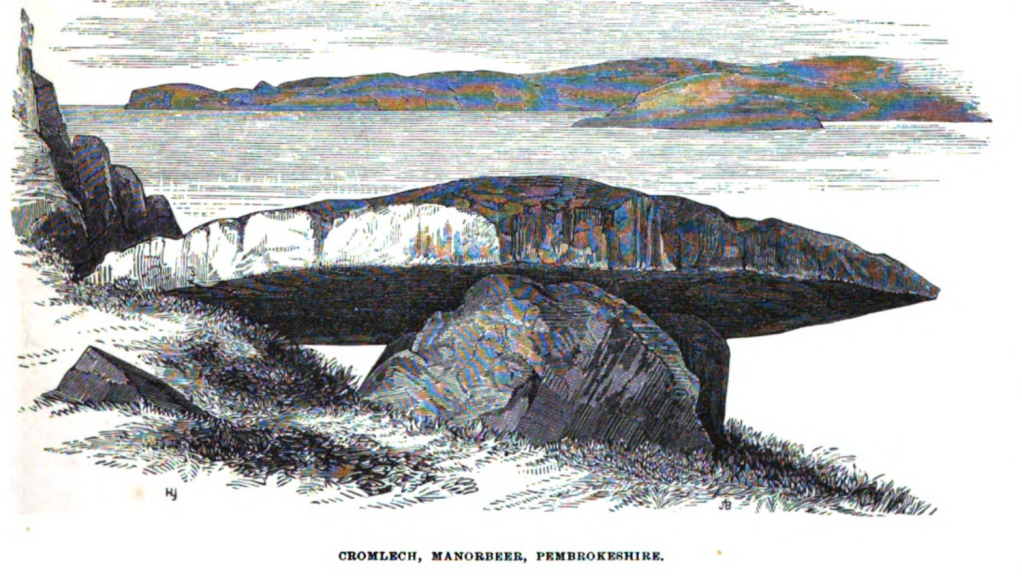

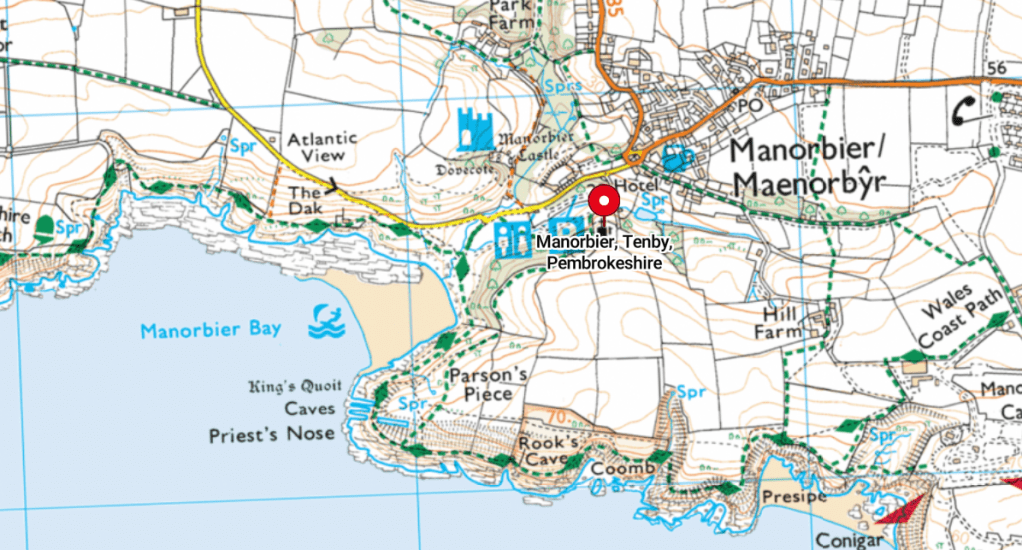

The King’s Quoit, a Neolithic Cromlech overlooking the beautiful Manorbier Beach.. Just a short walk from a car park overlooking the sea. The capstone is a massive slab of maroon sandstone, raised upon two small uprights.

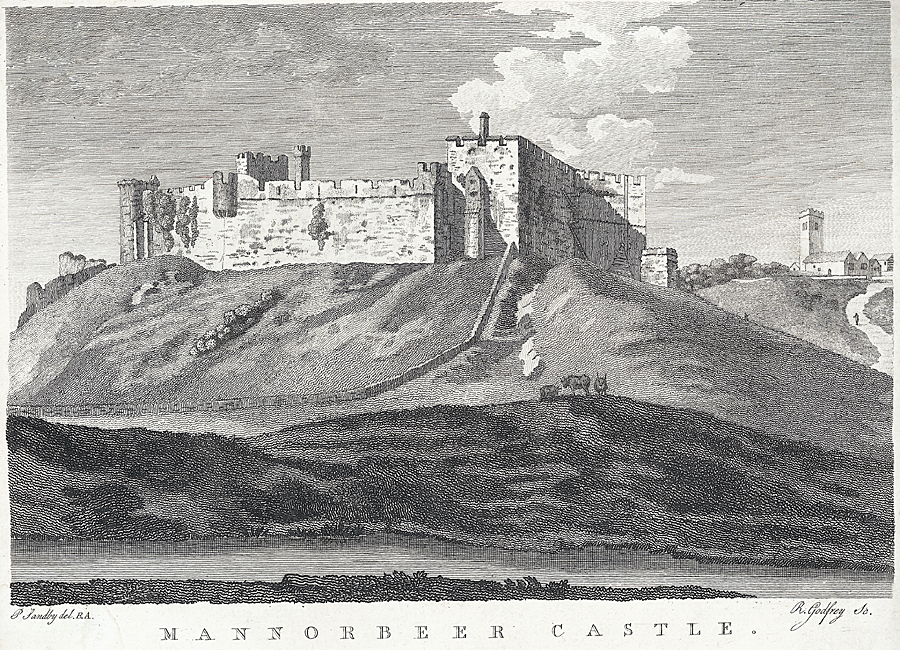

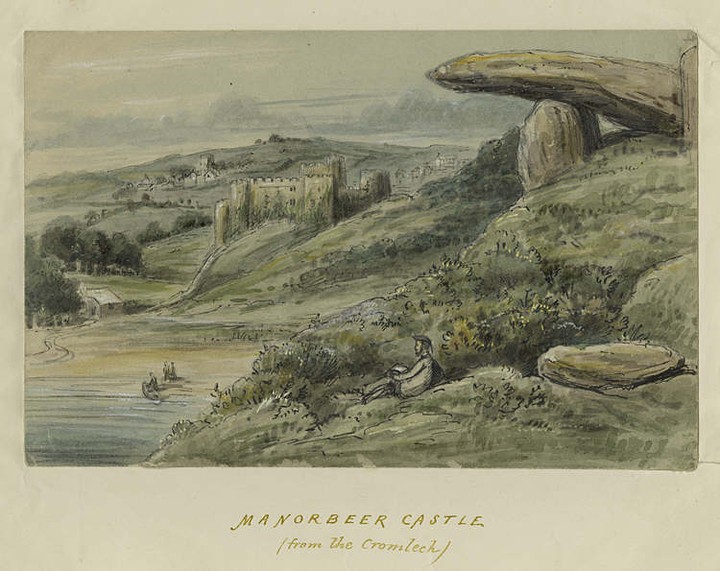

As you walk across the sand towards the Coastal Path up the cliffs, you can look inland towards the village and see Manorbier Castle.. Founded in the late 11th century by the Anglo-Norman de Barry family. In 1146, the fourth and youngest son of de Barri, Gerald of Wales – priest and historian – was born here. He travelled extensively and recorded his journeys..

He wrote of his birthplace: “In all the broad lands of Wales, Manorbier is the most pleasant place by far.”

In 1871, Sir Gardner Wilkinson makes note of this cromlech when discussing whether or not these kind of structures would have once had a covering mound. The above illustration is also provided: “…Some, too, like that of Manorbeer, in Pembrokeshire, are so placed as to leave no room for a carn, or a tumulus. If not so overed, cromlechs, it is true, would be the very worst and most exposed kind of sculchre, and probability is therefore in favour of their having been buried and concealed ; but it is not from probability that I have been induced to alter my former opinion of cromlechs being without a mound ; and I have since obtained direct evidence of their being so buried, from seeing two at Marros, on the south-west border of Caermarthenshire, where the stone which covered them still form part of their carn or tumulus….” To read the full report – https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924087796771&seq=304&q1=manorbeer

In Archaeologia Cambrensis, in the same year he also has a record of the cromlech: “Its outer end rests on two low supporters standing nearly at a right angle with each other, and the inner end rests partly on the ground, partly on another block, immediately below a wall of rock or line of stone slabs… there appears to be little room for a mound or earn to stand over this cromlech, as the ground falls very suddenly from it on two sides”

The Reverend Gilbert Smith, Rector of Gumfreston, in 1849, wrote

“Descending from the castle to the shore, and climbing the rock on the left hand,

about high water mark, a narrow path conducts us to a cromlech, situated near the

verge of the cliff. This memorial of a distant era had three supporters from one of

which it has slipped – and now inclines to the south. The supported stone itself is

about nineteen feet long and sixteen broad.”

In 1865, antiquarian ‘HLJ’ wrote:

“The singular beauty and romantic wildness of the little bay at Manorbeer is

another distinguishing ‘accidental’ of this cromlech; while not far above it, in the hill,

opens one of those yawning chasms going right down through the vertical strata to the

sea beneath, which are some of the most remarkable features of the district.”

This type of dolmen is classified as an “earth fast” chambered monument, and is thought to have likely never been covered with a mound.

Cummings and Whittle (2004) in Places of Special Virtue, which combined and built on Tilley (1994) and Barker‘s (1992) gazetteer The Chambered Tombs of South-West Wales points out that restricted visibility due to a local high horizon is a common feature among this group type of monument.

The authors compare these restricted-view, western megalithic constructions with other types of monument of comparable age elsewhere in the UK, such as henges, which usually have a more or less unrestricted view all round, and suggests that selecting a location which created a strongly one directional outlook was deliberate and possibly meaningful.

Leave a comment