LLawhaden in Pembrokeshire, Wales. This village not only contains the remains of an impressive castle, but also a medieval hospital and chapel, making this an important place for understanding the growth and decline of medieval towns.

During the Middle Ages, the diocese of St Davids was the largest and richest in Wales. It’s bishops were not only prominent in the church but also powerful in the affairs of state. As a reflection of their power and status, the bishops built on a grand scale and this Bishop’s Road pilgrimage route journeys from their castle at Llawhaden to their palace at St Davids. The castle would not only be a defensive building, but also a center for managing church properties in the region.

The Castle:

It is believed that the castle began as an earth and timber structure at some time in the 12th century and was in the possession of the Norman Bishop Bernard who served as chancellor to Queen Matilda before being suddenly made Bishop of St Davids on September 18, 1115, after King Henry I persuaded the chapter of St Davids.

The castle was in the hands of several bishops during this time, including Gerald of Wales’ uncle bishop David Fitz Gerald around 1175. The castle would have provided adequate accommodation for the higher clergy and it is said that Gerald of Wales stayed in the castle whilst visiting his uncle.

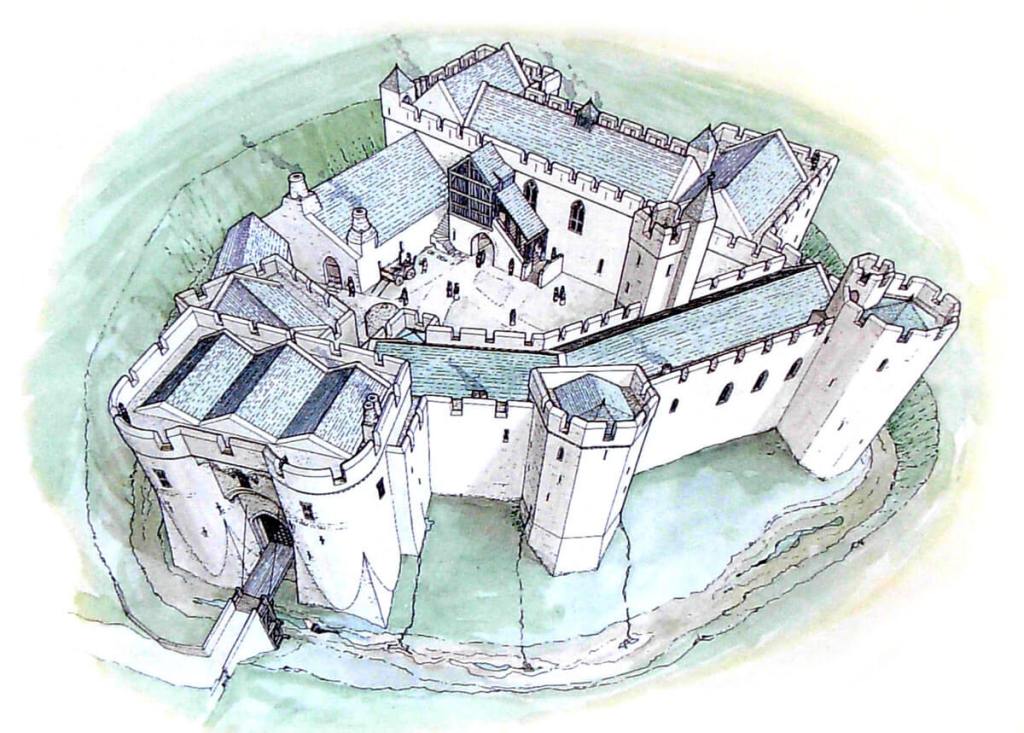

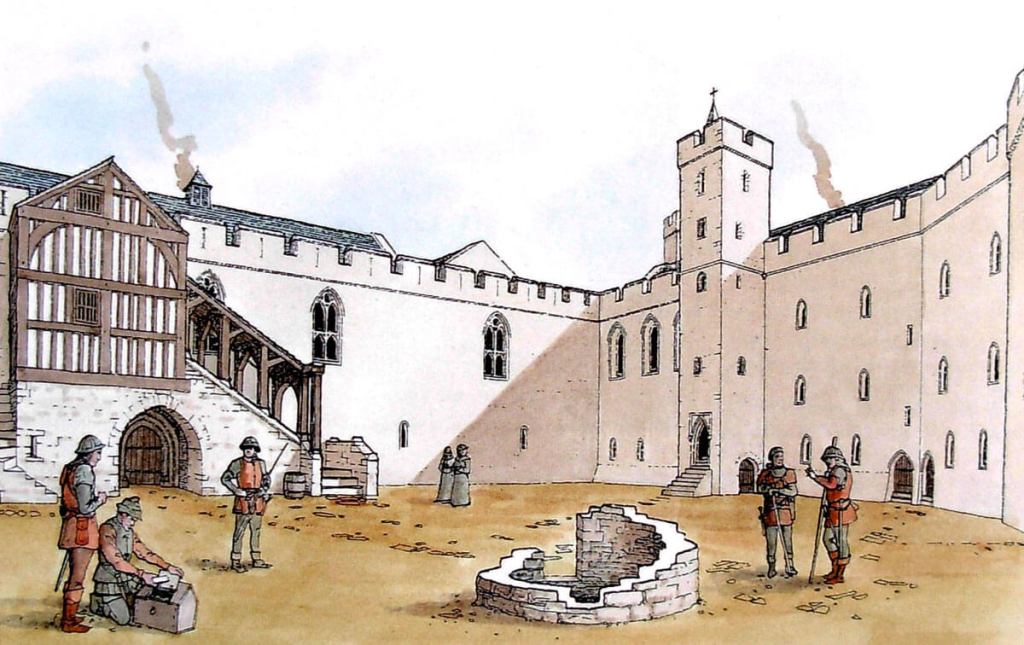

In 1192 the castle suffered a siege led by Lord Rhys, (a cousin of Gerald of Wales) which led to the defenses being fortified in stone. But it was Thomas Bek from his appointment as bishop in 1280 who transformed it into a major fortified mansion.

The bishop began life in Edward I’s royal household by working as keeper of the wardrobe in October 1274. He was a trusted servant of the king and was custodian of the Great Seal temporarily in 1279. Bek became bishop of St Davids in 1280 and between then and his 1293 death, worked on the castle and founded two collegiate churches and two hospitals. His work on the castle included the complex hall block, kitchen, buttery and pantry, stone-vaulted under crofts and the bishop’s chambers which were elaborately adorned, including latrines.

The Prison:

The castle also served as a bishop’s prison and place of conducting trials. In the basement of the eastern tower (Chapel Tower) there was a prison, and in the ground floor (accessible from the courtyard) a polygonal chamber. Entrance to the unlit prison cell was only possible through a hatch in the ground floor, while from the ground floor chamber a narrow corridor in the thickness of the wall allowed access to the small latrine.

It is said that in 1488, Bishop Hugh Pavy officiated the trial of William ap Hugyn, a parish clerk who was accused of robbing and violating a woman named Gwenillian. He pleaded innocence and his only punishment was to pay expenses to the castle dungeon’s keeper.

In 1503, a woman named Tanglwys was said to have been detained in the castle, and Thomas Wyiott stormed the castle to free her.

The castle was abandoned in the 16th century, and a quantity of the stones removed for local buildings.. Despite this, what we have left today is still an impressive site.

The following is quoted from ‘A Historical Tour Through Pembrokeshire’ by Richard Fenton, published in 1811:

“Of late years much of this venerable ruin has been plundered most shamefully and unnecessarily, to supply materials for repairing the roads, particularly in a country abounding with rab and stone of various sorts fit for that purpose; and it is to be lamented that the bishops of St. David’s are not induced to prohibit such depredations on that majestic structure, from which they derive their title to sit in the house of peers.

Indeed, the removal of those relics which give such dignity and picturesque effect to this and many other counties of Wales would be a serious injury, as they are irresistible magnets, attracting travellers to visit them, whereby the country cannot fail to be benefited in a high degree; and yet so little attention is paid to them, that views taken of many fifty years ago would hardly be known, so much in that time have they suffered by wanton dilapidation, more than by the mouldering consequence of age.

Bishop Barlow stripped the castle of Llewhaden and palace of St. David’s of their leaden roofs, as well as all his other palaces of every thing that could be converted into immediate profit, to furnish him, by the dilapidation he himself had occasioned, with a plea for removing the see to Carmarthen, or at least for contracting the episcopal establishment.

Archbishop Abbott, 1616, granted a licence to Bishop Milbourne to demolish the castle of Llewhaden, and also the hall, chapel, cellar, and bakehouse, belonging to the palace of St. David’s, in short, to perfect what Barlow had begun ; but Milbourne’s translation to Carlisle prevented the execution of this (I might almost say) sacrilegious design, and Llewhaden still remains, though in ruined pride, a most picturesque object to attract the notice of every traveller of taste, as it bursts on his view in descending from the village of Robeston to Canaston with a superb foreground of wood and water, itself on an eminence, and happily backed by the finely undulating line of the Presselly range of hills.” – https://archive.org/details/b22013179/page/316/mode/2up?ref=ol&view=theater&q=lawhaden

Medieval hospital & chapel remains:

There is a considerable amount of open space in Llawhaden, land which was laid out as burgage plots in the late thirteenth century and then abandoned and left undeveloped since the mid-fourteenth century.. making it an important area for addressing research themes on town plantation and town decline.

[A burgage was a town (“borough”) rental property, owned by a king or lord. The property (“burgage tenement”) usually, and distinctly, consisted of a house on a long and narrow plot of land, with a narrow street frontage. Rental payment (“tenure”) was usually in the form of money, but each “burgage tenure” arrangement was unique and could include services.]

A triangular intersection of four small roads 200m to the west of the castle is assumed to be the site of the medieval marketplace. The remains of the medieval hospital lie at the west end of the village.

“In 1281 Bek granted licences for Llawhaden to hold a weekly market and two annual fairs. In 1287 he established a hospital under the rule of a prior charged with the care of ‘pilgrims, paupers, orphans, the old, weak and infirm’, and endowed it with land.

Settlers, mostly English, were encouraged to immigrate to the new town and by 1326 126 burgesses held 174½ burgage plots, making it one of the largest towns in southwest Wales.

Market dues, tolls and rentals and leases made Llawhaden the most lucrative of the bishop’s holdings. Building works are recorded at the castle in the second half of fourteenth century and later, but history is silent on the later fate of the town.

It is assumed that its decline was as dramatic and rapid as its rise and that it did not survive the European-wide population crash of the mid-fourteenth century. In 1501 only the chapel element of the hospital remained active and this was dissolved in 1535, by which time Llawhaden was little more than a village.” –https://www.dyfedarchaeology.org.uk/wp/discovery/projects/llawhaden/

Here is the video we made covering the history of Llawhaden –

Leave a comment