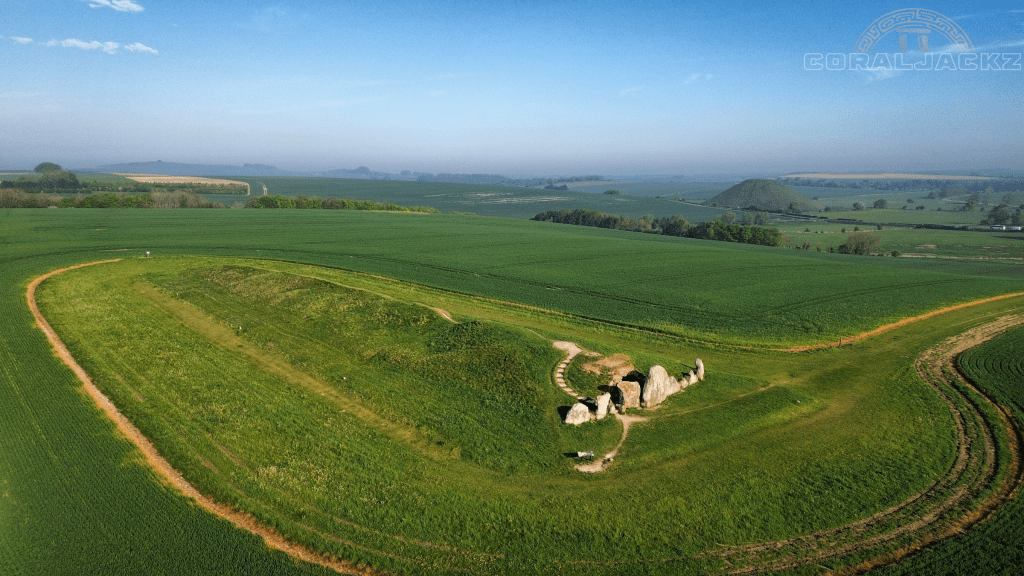

Located in Wiltshire, England. West Kennet is the largest chambered long barrow in Britain. The monument as we see it today is the result of reconstruction work after excavations took place in the 1950’s.

Radio carbon dates from remains found during excavations in the 1950’s go back as far as 3600BCE to 3700BCE. Experts believe that following its construction, over 5,500 years ago, the burial chambers were initially used for only a few decades, with the remains of over 36 people being deposited during this time of 30 to 50 years. Dates from a secondary layer, separated by a covering of sarsen slabs and chalk rubble, suggest that deposits and further infill continued for around a thousand years before being completely filled in and sealed off.

We have a video in which we cover the known history, excavations and restoration of the monument –

Early records:

Around 350 years ago, the Famous Antiquarian John Aubrey travelled this area, visiting ancient sites and recording his findings, in a series of manuscripts known as Monumenta Britannica …

The exact date of his visit to West Kennet remains unknown, and there are doubts that he is actually describing the same monument, but the manuscripts are said to have been written between 1665-1693… and you can view them in full on digital bodleian.

In a section titled barrows, we have a page of three similar barrows and at the bottom is the one he describes as West Kennet, the text reads “on the brow of the Hill, south from West Kynnet, is this monument, but without any name. It is about the length of the former [referring to a barrow near Marlborough]; but at the end, only rude greyweather-stones tumbled together; the barrow is above half a yard high.”

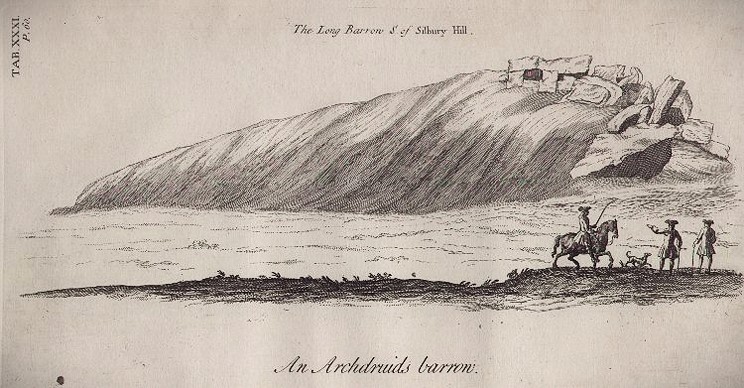

A few decades later, around 1725 William Stukeley included this sketch West Kennet Long Barrow in his book Abury, a temple of the British druids, with some others described. He refers to it as south long barrow … “near Silbury-hill, south of it, and upon the bank of the Kennet. It stands east and west, pointing to the dragon’s head on Overton-hill. A very operose congeries of huge stones upon the east end, and upon part of its back or ridge; pil’d one upon another, with no little labour: doubtless in order to form a sufficient chamber, for the remains of the person there buried; not easily to be disturbed. The whole tumulus is an excessively large mound of earth 180 cubits long, ridg’d up like a house. And we must needs conclude, the people that made these durable mausolea, had a very strong hope of the resurrection of their bodies, as well as souls who thus provided against their being disturbed.”

Roughly a century later, Richard Colt Hoare documents his research in this parts, published in two volumes between 1812 and 1821… but although he includes some lovely plates of Marlborough mound and Silbury hill… he simply describes it as the “most remarkable of the stupendous long barrows in the neighbourhood of Abury. According to the measurement we made, it extends in length 344 feet; it rises, as usual, towards the east end, where several stones appear above ground; and here, if uncovered, we should probably find the interment, and perhaps a subterraneous kistvaen…”

A few decades later, in 1849 it was described by Dr. Merewether, Dean of Hereford “At the east end were lying in a dislodged condition at least thirty sarsen stones, in which might clearly be traced the chamber formed by the side uprights and large transom stones, and the similar but lower and smaller passage leading to it; and below, round the base of the east end, were to be seen the portion of the circle or semicircle of stones bounding it.”

Thankfully, his visit to West Kennet Long barrow, and a couple others, was “at so late a period of my Wiltshire sojourn, that I could not indulge in the gratification of examining them. It is a satisfaction to mention these three, in the hope that it may lead to the disclosure of their interesting contents at some future day.” So, it’s quite plausible that between the likes of Dr toope, various treasure seekers and a host of enthusiastic antiquarians, more and more of the inner passage and chamber were becoming visible.

In 1859 a limited excavation of the east end of the barrow was undertaken by Dr John Thurnham. Thurnam was fascinated by the study of human skulls and wanted to find specimens to include in his book, Crania Britannica: Delineations and Descriptions of the Skulls of the Aboriginal and Early Inhabitants of the British Islands, published in 1865. He found six skeletons during his excavation.

The following is from – ‘Examination of a chambered long barrow, at West Kennet, Wiltshire’ from the Royal College of Surgeons of England published in 1861:

“It has been surrounded by a complete peristalith, which according to John Aubrey, was nearly perfect in the 17th century, but of which fragments only now remain. Near both the north-east and south-east angles of the tumulus, two stones remain standing, and there are two or three others which have fallen or been broken away, and are now partially buried in the turf.

The entire barrow was no doubt originally surrounded with a ring of these stones, just as was the great chambered cairn of New Grange in Ireland. Some of the chambered long barrows of the west of England, as those of Stoney Littleton and Uley, have been enclosed by a dry walling of stone in horizontal courses, carried to a height of from two to three feet. The surrounding wall of the long barrow at West Kennet, as is the case with similar tumuli in this district, united both methods, and was formed by a combination of ortholithic and horizontal masonry. .

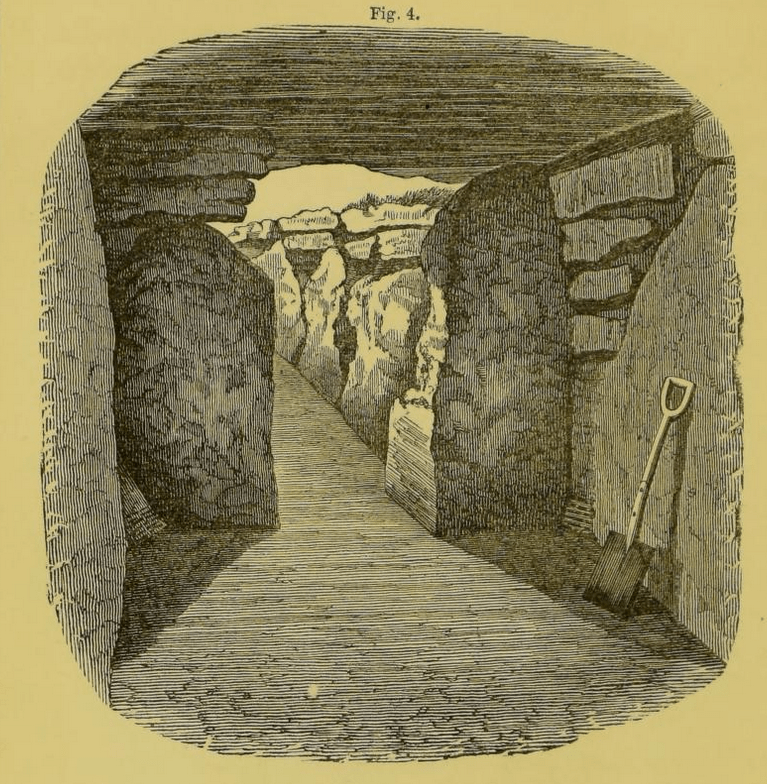

This was ascertained by digging between the stones at the north east angle of the tumulus. Here, at one spot, were several tile like oolitic stones, the remains no doubt of a dry walling, by which the spaces between the sarsen ortholiths had been filled up, after the manner shown in the accompanying woodcut (fig. 3), though, carried probably to a greater height. In the long barrow on Walker Hill (Alton Down), near its east end, is an upright of sarsen, and below the turf at a little distance on each side, another fallen ortholith of the same stone was uncovered. Between these, on each side of the remaining upright, a horizontal walling of oolitic stones was found neatly faced on the outside, five or six courses of which remained undisturbed.

Permission had not been given to move any of the stones on the surface, and operations were confined to the neighbourhood of the presumed chamber, and to digging on the east and west sides of the three large cap-stones. Omitting the details of the excavation, it may suffice to state that the chamber was entered from the west end, and was found to be formed of six upright sarsen stones, covered by three very large blocks of the same, and having a gallery entering it from the east, similarly constructed. (Figs. 4, 5, 6.) The chamber was about eight feet in length, by nine in breadth, and nearly eight feet in clear height. On clearing out the earth and chalk-rubble with which it was filled, the chamber was found to contain six skeletons, all, so far as could be made out, in the crouched or sitting posture, — five being probably of males from 17 to 50 years of age, and the sixth that of an infant. With one exception, they were of less than middle stature. Two of the skulls were remarkable for distinct traces of fractures, unequivocally inflicted before burial and probably before death. Bones of various animals used for food were found, including those of the sheep or goat, ox of a large size, roebuck, boars and other swine. There were very numerous flakes and knives of flint, some of which were circular and elaborately chipped at the edges : one only had been ground (fig. 7), and may have been used in flaying animals. There were two or three large mallets or mullers of flint and sarsen stone, part of a rude bone pin, and a single hand-made bead of Kimmeridge shale. The fragments of coarse but ornamented pottery were remarkable for their number and variety (figs. 9, 10) ; and in three of the four angles of the chamber there was a pile of such, evidently deposited in a fragmentary state, there being scarcely more than two or three portions of the same vessel. One small vase had been perforated at the bottom and sides. (Fig. 11.) In the central part of the chamber was a shard of pottery, perhaps Homan, (fig. 12) ; and a fragment undoubtedly such, was turned up at some depth outside the chamber, near its western end, — affording a probable indication that it had been searched during the Roman period. By whomsoever opened, its contents had been but partially disturbed ; as was proved by the condition and order of the skeletons, and by the presence of a defined layer of black unctuous earth immediately above them. Not a bit of burnt bone or other sign of cremation was met with ; there were no traces of metal, either of bronze or iron ; or of any arts for the practice of which a knowledge of metallurgy is essential.

The upright and covering stones, of which the chamber and its appendages were formed, were of the hard silicious grit or sarsen stone of the district ; the horizontal masonry (of which there were traces between the uprights at the bottom of the chamber and gallery, as well as surrounding the base of the mound), was of tilelike stones of calcareous grit, the nearest quarries of which are in the neighbourhood of Caine, about seven miles to the west. The skulls, of which four were nearly perfect, are more or less of the lengthened oval form, with the occiput expanded and projecting, and present a strong contrast to skulls from the circular barrows of Wiltshire. They confirm the observation previously made, that crania from the long chambered tumuli of this part of Britain are usually of a narrow and peculiarly lengthened form. The forehead is mostly low and narrow ; the face and jaws, as compared with the other ancient British type, decidedly small.

The principal skeleton, to which the skull figured in “Crania Britannica,” (pi. 50) belonged, was that of a man about 35 years of age. It was deposited in the north-west angle of the chamber, with the legs flexed against the north wall. The thigh bone measured 17f inches, giving a probable stature of 5 feet 5 inches. The skull faced the west. The lower jaw was found about a foot nearer to the centre of the chamber, as if it had fallen from the cranium in the process of decay. Being imbedded in the clayey floor, the jaw was singularly well preserved, of an ivory whiteness and density, and even retained distinct traces of the natural oil or medulla. Near the skull was a curious implement of black flint — a sort of circular knife with a short projecting handle, the edges elaborately chipped. (Fig. 8.) The skeleton was perhaps that of a chief, for whose burial the chamber and tumulus were erected, and in honour of whom certain slaves and dependants were immolated. J.T” – https://archive.org/details/b22440021/page/n1/mode/2up?ref=ol

1950’s Excavation and Reconstruction:

Between 1955 and 1956, the West Kennet Long Barrow was subject to further excavation. This time led by Stuart Piggott and Richard Atkinson and was followed by reconstruction work. A BBC television episode of ‘Buried Treasures’, presented by Glyn Daniels, broadcast in 1955 was made about the excavation. I cannot find this episode sadly, but here is the link to the other episodes in the series – https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episodes/p017t7tn/buried-treasure

The excavation was mostly confined to the east of the barrow, to clarify the arrangement of the passage and chambers which were recorded by Thurnham. Piggott and Atkinson’s excavation identified all five chambers and recovered skeletal and dating evidence including Neolithic pottery and flint and stone tools. They also recovered Six bronze Roman coins, which were buried into the topsoil near the sarsen façade.. Raising the possibility of continued use of the mound.

We have recently acquired a copy of the full excavation report. We will update this page and upload a video on our Patreon soon – https://www.patreon.com/c/CoralJackz

Quoting Piggott: *All photos taken during this excavation and restoration that we could find are also on our Patreon page*

“When excavation began in the area of the known chamber and passage at the eastern end of the mound, practically the only stones which could be assigned to a function were those standing or leaning in an approximately straight line as a façade to the barrow. Outside these lay an enormous recumbent stone which we now know to have been the central blocking-stone, fallen outwards, and westwards of the façade, piled on the eastern slope of the barrow, lay a meaningless jumble of blocks, two of which were in fact the undisturbed cap-stones of the two northern chambers, and a third the displaced cap of the south-east chamber. As the removal of obviously non-structural stones, and the excavation of the area proceeded, it became clear that considerable wreckage had taken place over what was finally discovered to be the blocked forecourt and the passage immediately westwards of it ; the cap-stone of the south-east chamber, as we have seen, had in fact been dragged off southwards.

As Stukeley’s drawings show us that the site was already in this state by 1723 (the south-east cap-stone was certainly as we found it in 1955, and the other stones, less surely identifiable, seem also to be in the same state), the wrecking must have taken place before that date. The most likely suspect is Dr Toope, of whose activities Stukeley was told, and who certainly dug in what may have been a Saxon cemetery near The Sanctuary for human bones to make ‘ a noble medicine that relieved many of my distressed neighbours ‘. If he had hoped for further bones at West Kennet, the peculiar circumstances of the deliberate filling of the burial chambers in antiquity prevented him ; the disturbance over the eastern chambers extends to a depth of 3 ft. only, leaving 5 ft. of undisturbed filling before the primary burials on the chamber floors could be reached.

The plan of the burial chambers on complete excavation showed a symmetrical composition, with a wide passage some 23 ft. long leading to a polygonal western or terminal chamber, and with two pairs of lateral chambers opening from it, three of these being approximately rectangular in plan, while one (the north-west) is polygonal. The proportions are massive : the terminal chamber is 9 ft. square and the others proportionately large. The construction is of blocks of local sarsen joined by panels of dry-stone walling.

The cap-stones are carried on two or more courses of sarsen corbels above the uprights at a height of 8 ft. above the floor in the two eastern chambers and in the terminal (western) chamber, and 6 ft. in the south-west and north-west chambers. These two chambers had their entrances blocked by small sarsens just over 3 ft. high set on the old surface and not in stone-holes as are all the structural uprights (PLATE xxv, a). The passage opens on to a shallow semi-circular forecourt 30 ft. across and about 7 ft. deep, which at its extremities joins to an approximately straight façade 20 ft. long on north and south, forecourt and façade being constructed of sarsen uprights joined by dry- stone walling in the same manner as the passage and chambers. The core of sarsen boulders already described as forming the spine of the mound continued round the chambers, and seems to have been held by revetment walls immediately behind the forecourt, this and the façade being backed by chalk rubble.

No cap-stones of the passage at this point remained in situ. It could be established, however, that two massive upright stones had stood in the forecourt, more or less continuing the line of the sides of the passage, and on each side of these the forecourt was filled with a blocking of sarsen boulders. Whether these uprights had carried a lintel could not be decided owing to the destruction at this point. Immediately in front of the uprights three large stones had been set so as to continue the line of the façade as a chord of the forecourt arc. The central and southern of these stones has fallen outwards and lay flat, the northern was leaning outwards and had been partly destroyed. The central stone measured 13 by 10 ft. and when re-erected in its original stone-hole rested against the two uprights within the forecourt area. The whole of this construction must be interpreted as an exceptionally massive forecourt blocking set up at the final closing of the tomb.

Professor Wells was able to demonstrate some very curious features in the circumstances of the West Kennet burials. In the first place there are not enough skulls to go round, and more lower mandibles than skulls. This (as he says) suggests that skulls were removed after the remains were reduced to skeletal form, in some instances leaving the lower jaw behind, and still more odd is the fact that there is a similar shortage of the larger limb-bones, which may also have been removed from the tomb after burial.

It has already been mentioned that one of the skeletons in this chamber had a leaf-arrow- head associated with it. Otherwise, grave-goods in the normal sense were not present, but subsequent to the final deposition of burials (and after the presumed robbing of the tomb for skulls and long-bones) the chambers and passage were deliberately filled with irregular layers of chalk rubble, mainly clean but with many seams and patches (up to a foot or so in thickness) of rubble stained brown and black with charcoal dust and containing abundant potsherds, animal bones, flint flakes and occasional implements, bone points and other tools, and frequent beads made of bone, stone or perforated shell. A similar but less concentrated scatter occurred sporadically in the clean layers.

The filling had been carried up completely to the underside of the capstones, and one can only assume that the far chambers were filled first, those responsible for the process backing out in what would seem to us a rather undignified manner. The filling of the five chambers and the passage would amount to some 2,500 cu. ft. of material. The impression given by the mixture of dirty rubble and broken artifacts was that in part at least soil and rubbish had been scraped up from the floors of settlement-sites, or perhaps from temporary camping-places connected in some way with the funeral ritual.

All the foregoing finds occurred in the filling of the chambers and of the passage where this remained intact; for half its length this, and the western chamber, had been dug out by Thurnam and refilled in modern times. Except for one or two Peterborough sherds and a human skull and other bones already mentioned, the forecourt blocking contained no finds, nor was there any trace of ritual features or finds in the 20-ft. wide excavation made in front of the whole length of the entrance and façade.

The results of the new excavations at the West Kennet Long Barrow have (as so often is the case) cleared up certain difficulties but raised many new problems. The recovery of the plan of the burial chambers shows that far from dealing with an abnormality we have in fact the finest and largest example so far known of a tomb-type well known in the Severn- Cotswold group of chambered cairns, and hitherto best represented by Notgrove and Uley in a form most nearly comparable to West Kennet, and with other characteristic variations on the same basic plan in Stoney Littleton, Nympsfield or Parc le Breos Cwm: Wayland’s Smithy, A remarkable feature at West Kennet is the comparatively great height of the passage and chambers-6 to 8 ft. Whether we call such tombs passage-graves or gallery-graves seems a semantic irrelevance, but the fact which is of importance is that comparable tomb-plans do occur in a restricted area of Western France around the mouth of the River Loire.

The placing of the burial chambers at West Kennet at one end of an enormously long mound, part sarsen cairn and part rubble thrown up from flanking quarry-ditches, again emphasizes the complexities of tradition combined in our chambered long barrows and cairns. Here one has surely to look to the unchambered long barrows whose origins may well lie not in the west of Europe, but rather eastwards of the British Isles in the North European plain. The Windmill Hill culture, which not so long ago looked so deceptively homogeneous, may well turn out to be a complex affair with multiple origins in many European Neolithic traditions.

The phenomenon of the deliberate secondary filling of the chambers and passage seems hardly to have been recognized as a feature in the chambered tombs of the British Isles. On the other hand, it must be remembered that many of our better-known tombs have been, at the time of excavation, long roofless and ruined; both Nympsfield and Notgrove are examples of this state of affairs, and chamber filling could have existed. Nor can we be sure that the filling present in less ruined sites need always be the result of the later collapse of walling, etc., and, indeed, such sites as Pipton, where Dr Savory found that one chamber had in all probability been deliberately filled with clean earth, and another probably filled in a similar manner, shows a comparable situation, though in this case without the inclusion of artificts.1° At Ty-isaf, too, Professor Grimes found the chambers full of stone debris, perhaps as a result of later ruin, perhaps not.

And apart from these and other results of concern to the professional archaeologist, the work of conservation and judicious restoration which the Ancient Monuments Department of the Ministry of Works has carried out since the excavations has provided the general public with an opportunity of seeing one of the most magnificent and impressive of our collective chambered tombs. To see the monumental facade with its huge blocking stones at the entrance, and to walk into the great burial chambers, is an experience which brings home to one the architectural capabilities of those builders in massive stones who, before 2000 B.c., were already in North Wiltshire mastering the basic techniques which were to be used by their successors at Avebury and at Stonehenge.”

Reconstruction:

During reconstruction work at the site following this excavation, the sarsen stones around the east entrance and many of the capstones to the main passage were re positioned. Many stones inside were re positioned so that the chambers could be open to visitors. Flat concrete roofs were also added as well as ‘glass roof lights’ to allow daylight to illuminate the interior.

“It is certainly possible that, although Piggott used a numbering sequence for the stones identified and moved during his excavations, the same number sequence does not appear to have been used during the reconstruction. Records made during the period of reconstruction indicate that communication between Piggott and the reconstruction team from the Ministry of Works was not all that it could have been.”

“It is evident that the 1956 reconstruction of the mound comprised a total reconstruction of the upper structure of the passage and chambers above the height of the orthostats (Richards 2010). Records made at the time clearly indicate that the reconstruction scheme was not to conserve the monument as it was before Piggott’s excavation (a mainly open topped ruin) but to reconstruct the barrow as it may have appeared after its construction during the Neolithic. To accomplish this, the structure was almost entirely recreated above orthostat level using not only stones won during the excavations but also stones imported from nearby. This recreated structure was completed by the addition of modern concrete capping with glass roof lights to allow daylight to illuminate the interior. It is unclear to what extent, if any, an attempt was made to place any original stones in at least a semblance of their likely as built in the Neolithic position. It is, however, clear that the original excavators were not entirely happy with the final reconstruction, although it remains unclear exactly which elements attracted their ire.” – https://reports.cotswoldarchaeology.co.uk/content/uploads/2018/01/Binder1.pdf

LINKS AND RESOURCES:

John Aubrey, Monumenta Britannica, ~1665 to 1693 – https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/search/?q=Monumenta+Britannica

William Stukeley, Abury, a temple of the british druids, with some others described, ~1724 – https://www.gutenberg.org/files/64626/64626-h/64626-h.htm#tab_XXX

Sir Richard Colt Hoare, The Ancient History of Wiltshire, Vol. 2, ~1812 – https://apps.wiltshire.gov.uk/communityhistory/Book/Chapters?bookId=20

John Merewether, Diary of a dean, ~1851 – https://archive.org/details/b24885721/page/2/mode/2up

Dr John Thurnam, Excavation Report, ~1861 – https://archive.org/details/b22440021/page/2/mode/2up?ref=ol

Stuart Piggott, The Excavation of the West Kennet Long Barrow: 1955-6 – Behind Paywall – https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquity/article/abs/excavation-of-the-west-kennet-long-barrow-19556/5F82CC629FB5D8ACDDB7F6246CD00164

Radiocarbon Results – Talking About My Generation: the Date of the West Kennet Long Barrow – https://clok.uclan.ac.uk/id/eprint/10754/1/10754_wysocki.pdf

Life of Stuart Piggott – https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/documents/1412/97p413.pdf

Wiltshire Museum Collection – https://www.wiltshiremuseum.org.uk/search-the-collections/?s=west+kennet&page=1

Report from 2012 – Archaeological Watching Brief Undertaken by Cotswold Archaeology – https://reports.cotswoldarchaeology.co.uk/content/uploads/2015/03/3916-west-kennet-eval-12227-complete.pdf

Report from 2016 – Archaeological Watching Brief Undertaken by Cotswold Archaeology – https://reports.cotswoldarchaeology.co.uk/content/uploads/2018/01/Binder1.pdf

Leave a comment