This formation of stones dates back to between 2,000-3,000 BC.. the late Neolithic or early Bronze-Age. Some believe that these stones have been rearranged at some point, and were once part of a stone circle, up to 18m in diameter. It has also been suggested that the holed stone could have been a capstone for a ‘cairn’ which lies southeast of it.

Dr. William Borlase records the site in Antiquities, historical and monumental, of the county of Cornwall, 1767 – https://archive.org/details/bim_eighteenth-century_antiquities-historical-_borlase-william_1769/page/n212/mode/1up?q=tol

The following is quoted from Guide to the Men-an-Tol Holed Stone and other nearby sites, by Ian Cooke, published in 1937:

“The Men-an-Tol monument consists of four stones; one fallen, two uprights about four and a half feet high, and between these a circular stone set on edge and pierced by a hole large enough for a person to crawl through. Its age is uncertain but it is usually assigned to the Bronze Age between three and four thousand years ago. The supposed change in the position of the stones is based on a plan made by the 18th century antiquarian Dr. William Borlase which shows a slightly different arrangement of the stones from the present day, but this could have been an error since his work contains several inaccuracies, notably a plan of Pendeen Fogou. Nevertheless, many smaller prehistoric standing stones have been re-erected or moved during their ‘lifetime’ and it would be unusual for the Men-an-Tol to be an exception – it was set into a concrete base at an unknown date.

Holed stones are found in many parts of the British Isles as well as in other countries of the world and together with Holy Wells they have retained the ideas and customs associated with them more tenaciously than any other type of ancient site. Beliefs connected with them are remarkably similar from the Orkneys to the far west of Cornwall. Most holed stones are found in sight of, or near to stone circles and many are in partnership with nearby standing stones to form a visual symbol of procreation. The ‘female’ holed stone may well have its ancestry in the early Stone Age societies some six thousand years ago when tribal ritual structures (the ‘quoits’ and ‘chambered tombs’) were constructed not only within a circular area but in some cases with a small aperture through which ancestral bones could be passed out for use in fertility rituals concerned with the continuation of the people, their animals and land. By the Bronze Age the building of such monuments was dying out but the contagious magic of the hole as having beneficial powers for the community was carried on in rituals connected with holed stones.

These stones have magical rather than astronomical use and it has been suggested that they were sited at places of exceptional earth energy in addition to being designed to receive the rays of the sun and the light of the moon at symbolically significant times of the year, nevertheless the Men-an-Tol does not appear to have any obvious links with sunrise or sunset positions although shadows cast may have been of more importance.

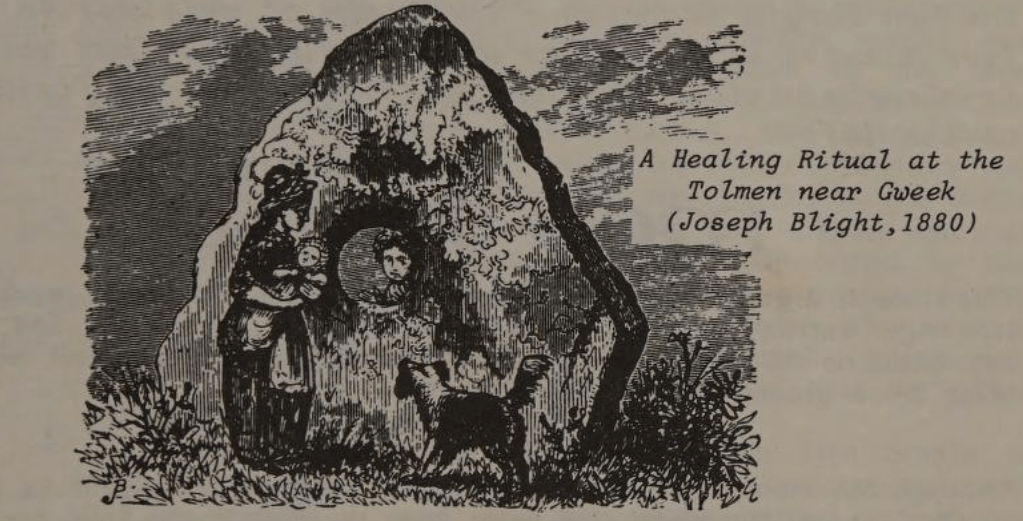

Stones, and in particular holed stones, have many traditions of fertility and healing associated with them because of energies believed to be stored within. In the British Isles, holed stones were thought to be particularly potent and small versions were often moved to where they were needed and were sometimes soaked in a liquid which was then used to convey the power of the stone to the patient. Offering of milk and blood were poured into hollows of stones and the rebirth of healing was symbolised by the sick person being passed through the holed stone. Children were passe through as an act of baptism to secure good health during their lifetime as well as to cure illness should this first effort be thwarted. Engagements might be sealed at the New Year by young people holding hands through the stones, a sacred ceremony which if broken resulted in the offender being outcast from society. Stones were considered to help in having an easy childbirth, to cure barrenness and to promote an abundance of crops and cattle.

Traditional rituals at the Men-an-Tol involved passing babies and children naked through the holed stone three times and then “drawn on the grass three times against the sun”, while adults were expected to pass through the stone nine times to achieve the desired benefits of healing and fertility, and it was generally appreciated that such rituals would only be effective at particular times of the lunar month. The Men-an-Tol was also visited for ceremonies concerned with divination using brass pins placed across the top of the stone and then observing their movements.”

The holed stone has been present in folklore for centuries, as people believed the stone exuded healing properties. Janet and Colin Board in their book ‘Mysterious Britain’, 1984, say that:

“Many of these stones are supposed to be helpful in curing certain illnesses, and children were once passed through the Men-an-Tol when they were suffering from rickets. Stones with holes big enough to crawl through, and with similar beliefs attached to them, can be found all over the world. There may once have been some benefits to be gained from such customs, …….certain stones can hold powerful currents passing through the earth, could not the hole serve as a focus for this power, which would pass into the body of, and give renewed vitality to, anyone climbing through the hole?”

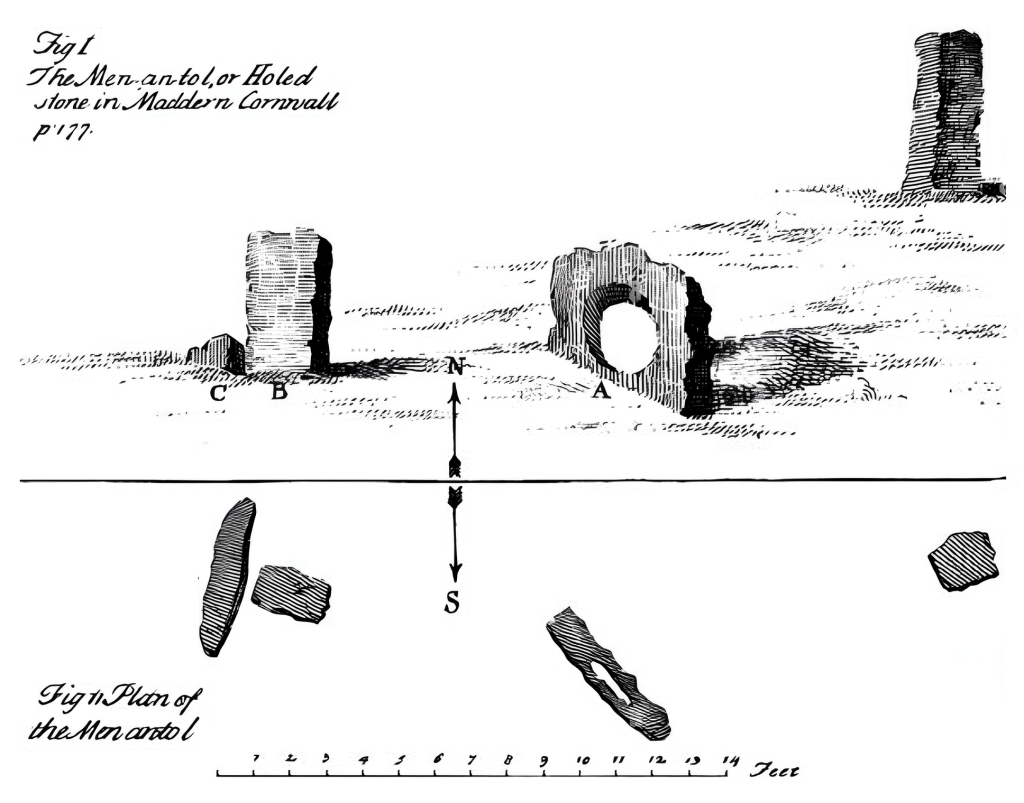

Illustration and plan of the Men-an-Tol as it was in the 18th century by William Borlase. Assuming Borlase’s drawing is accurate then the holed stone stood slightly out of alignment with the other two uprights, he was clear in his text that the stones formed a triangular setting in his time.

From stone-circles.org.uk: “The first drawings of the site come from the antiquarian William Borlase, who in the mid 18th century illustrated a triangular arrangement of four stones. Two of these were the present uprights with a further fallen slab just to the west and the holed stone set slightly further to the southeast than it is today and with a slightly different orientation. If Borlase’s plan is accurate then the stone stood with its long axis along a northwest to southeast line, the view through the hole being to the northeast and southwest. Borlase was at a loss to explain the meaning of the stones, being of the opinion that they ‘could be of no use, but to superstition. But to what particular superstious Rite appropriated is uncertain”.

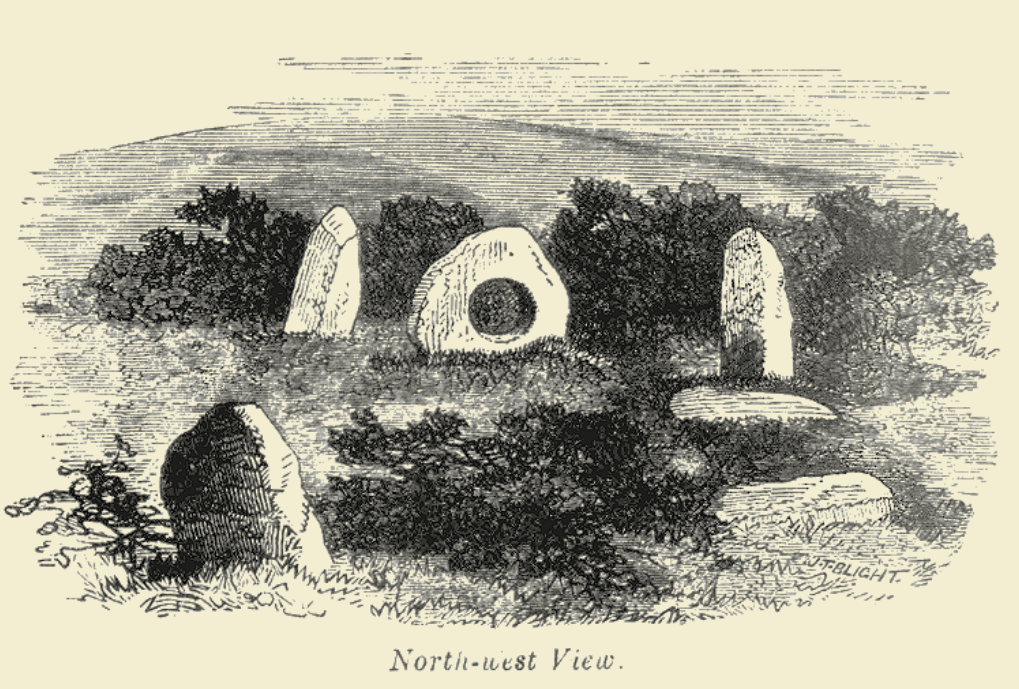

It seems that the holed stone was moved slightly in the following years as illustrations from the 19th century show it to be almost in line with the two uprights. In 1827 William Cotton shows the same four stones as Borlase but forty years later John Thomas Blight sketches a couple more stones to the west, one fallen and one upright.. Writing in 1864 Blight was also clear on what he thought the stones represented, he stated ‘From the positions of these stones it seems probable that they are the remains of a circle’.

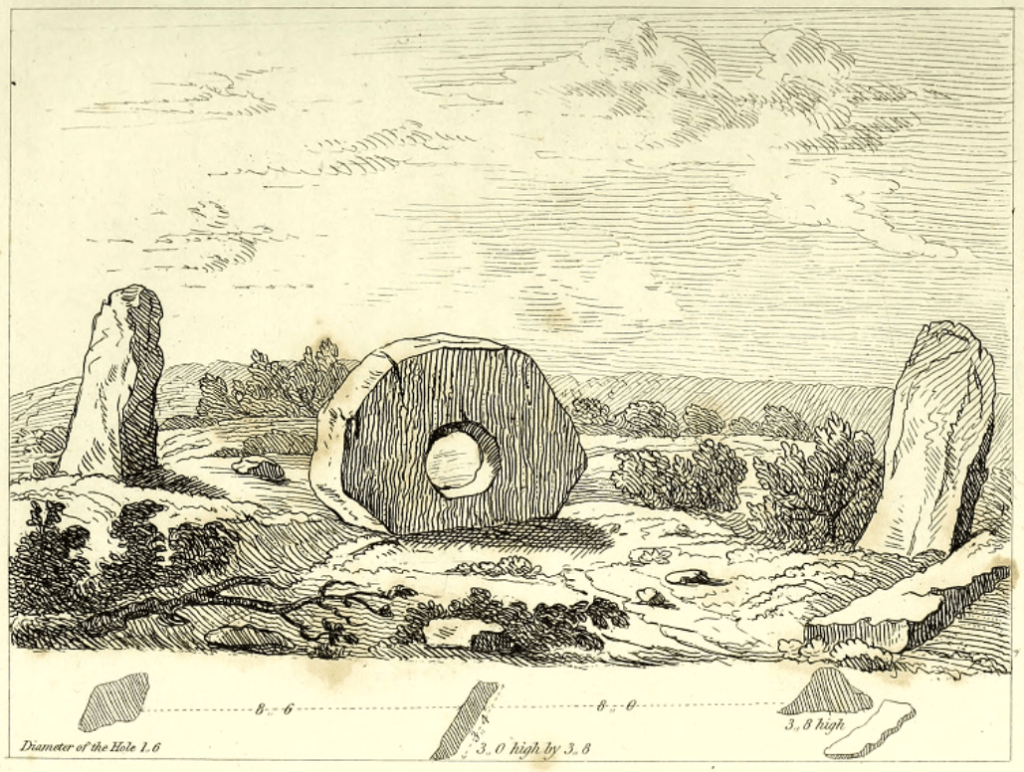

A fine sketch of the Men-an-Tol by William Cotton 1827, not withstanding the rather small hole in the centre stone. Cotton draws the holed stone in a slightly different position to Borlase, it is now more in line with the uprights.

Photograph of Mên-an-Tol taking in 1911, featuring a gentleman taking a nap by the stones.

Leave a comment