Other names – Senor, Senar Quoit

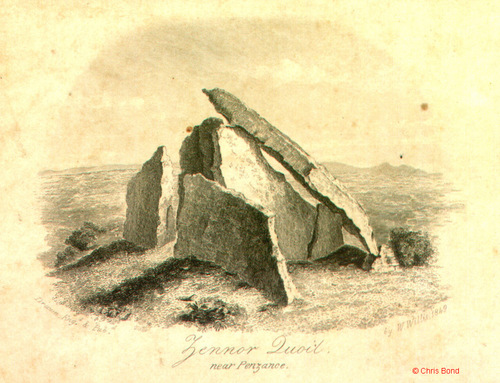

Zennor Quoit is an impressive neolithic monument in the village of Zennor (or Pluw Senar), in Cornwall. Unfortunately the massive cap-stone has fallen, which happened sometime between 1770 and 1765.

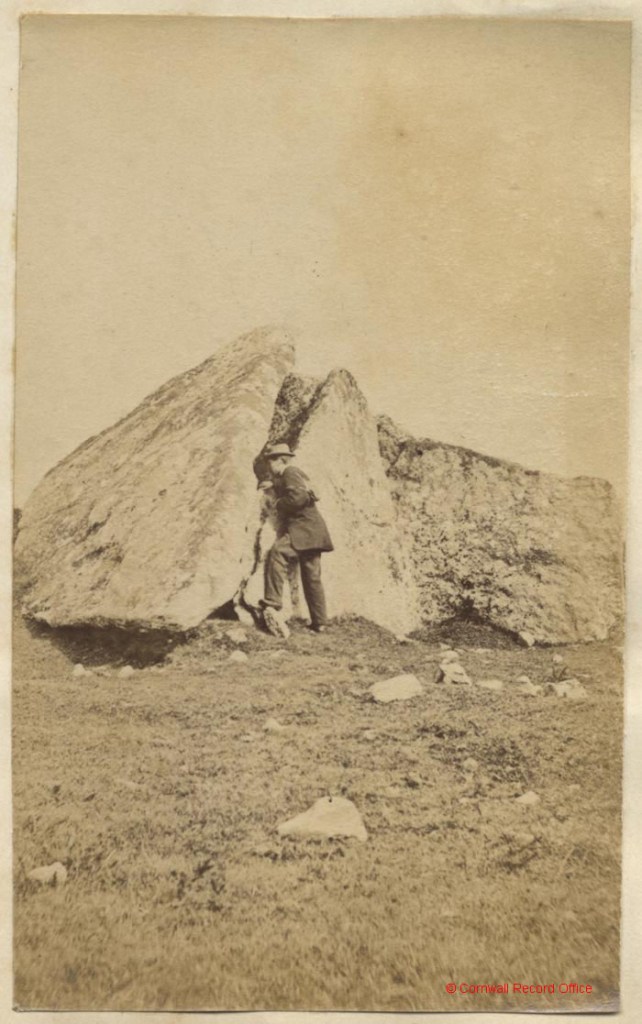

Legend claims that any stone removed from the Quoit will find its way back overnight. This was put to the test in 1861 when a farmer was attempting to break up the Quoit to build a cow shed. A local vicar and antiquarian William Copeland Borlase caught word of this and managed to bribe the farmer into leaving the monument alone. The upright stones next to the Quoit are the remains from this cow shed that was being built. You can also see the farmers’ drill marks in some of the stones.

“The chambered tomb, as it survives today comprises two chambers. The main trapezoidal structure has its long axis running just north of due east (75o); the west end, where the two long sides end, is 0.83m wide; the east end is 1.9m wide; and the whole is 3.16m long. The backstone (western) and frontstone (eastern) of the main chamber are both set in somewhat to give a chamber 1.43m long, 1.12m wide at the west end, 1.58m wide at the east end. An ‘antechamber’ sealed at the east end by the two impressive portal stones is 0.8m wide (E-W) and 1.95m long (N-S). The capstone is 5.33 x 2.9m and weighs c. 9.3 tons (Barnatt 1982, 246). The most satisfactory elevation drawings of the actual stones of Zennor Quoit are those published by Lukis in 1885 (see Herring 1987A Figs. 4 and 5). He also produced a useful reconstruction of the quoit with its capstone in position, based in part on Dr Borlase’s drawing but in the main on careful measurement of the surviving stones (see Herring 1987A Fig.5). “-https://hsds.ac.uk/data-catalogue/resource/7a559e6864c01002b6dd82290450e2518219c029f6d00ac32d225e7af0c38ca6

Description of the site from HistoricEngland.org.uk:

“The monument includes an entrance grave, situated close to the summit of a prominent ridge with coastal views overlooking Zennor Head. The entrance grave survives as seven upright massive earthfast stones, five of which define the edges of a rectangular chamber with two internal cross slabs. Two further stones form an impressive entrance fa‡ade and there is a further leaning, partially supported, capstone. All are enclosed within a low cairn measuring up to 12.8m in diameter. The chamber stands up to 2.4m high with the top of the capstone being approximately 3m high.

The entrance grave was first recorded by Borlase in about 1769. Some of the uprights were damaged before 1872 when they were cut to provide supports for a nearby cart shed; at least two of the stones still have visible drill holes, most likely dating from their attempted reuse. Before 1881 a local labourer dug out and smashed a pot and recovered a perforated Bronze Age whetstone. In 1910 R J Noall found flints, pottery and bones in a small hollow in the chamber floor, and shortly after 1918 cord impressed pottery was discovered in nearby rabbit burrows.”

Early records of Zennor Quoit:

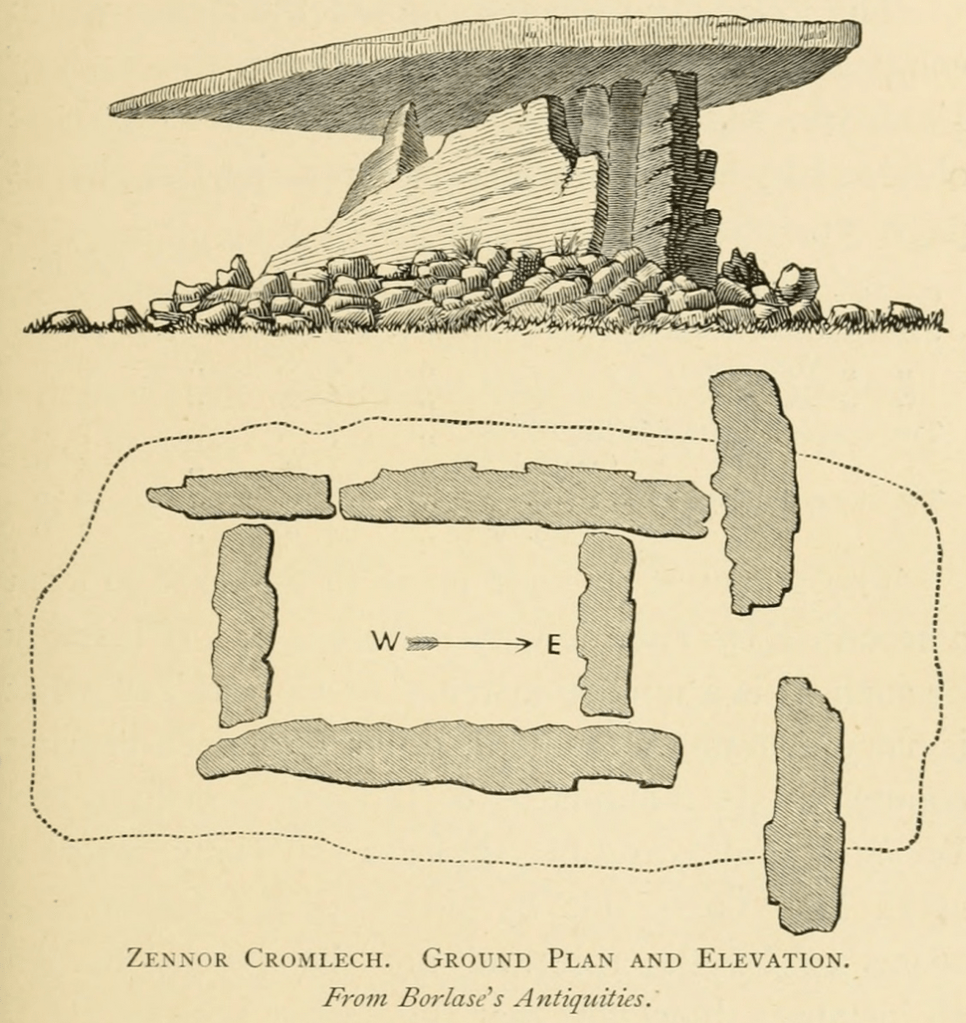

When Dr. William Borlase visited the site and records it in his Antiquities of Cornwall (1769), the capstone had not yet fallen:

“On the top of a high hill about half a mile to the East of Senar Church-Town stands a very large handsome Cromleh; the area inclosed by the supporters is exactly of the same dimensions as that at Molfra, viz. six feet eight inches by four feet, and points the same way, running East and West. The Kist-Vaen is neatly formed, and fenced every way, and the supporter marked number 2 in the plan, is eight feet ten inches high, from the surface of the earth in the Kist-Vaen, to the under face of the Quoit….

….The side stones of the Kist-Vaeen running on beyond the end Stone form a little cell to the East, by means of two stones terminating them at right angles. The great depth of this Kist-Vaen, which is about eight feet, at a medium under the plane of the Quoit, is remarkable; there is no stone in it, and the Stone-barrow fourteen yards diameter was heaped round about it, and almost reached the edge of the Quoit, but care taken that no stone should get into the Repository. This Quoit was brought from a Karn about a furlong off, which stands a little higher than the spot on which this Cromleh is erected ; and near this Karn is another Cromleh, not so large as that here described, in other respects not materially different.” – https://archive.org/details/bim_eighteenth-century_antiquities-historical-_borlase-william_1769/page/232/mode/1up?q=senor

The local postman-poet, C Taylor Stephens, wrote the collector of folk-stories Robert Hunt a note about Zennor Quoit which he had visited in 1859: ‘I inquired of a group of persons who were gathered around the village smithery (Zennor Churchtown), whether any one could tell me anything respecting the heap of stones on top of the hill. Several were in total ignorance of their existence. One said, ‘Tis caal’d the gient’s kite; thas all I knaw.’ At last, one more thoughtful,….gave me this important piece of information, – ‘Them ere rocks were put there afore you nor me was boern or thoft or; but who don it es a puzler to everybody in Sunner. I de bleve theze put up theer wen thes ere wurld wus maade; but wether they wus or no don’t very much mattur by hal akounts. Thes i’d knaw, that nobody caant take car em awa; if anybody was too, they’d be brot there agin. Hees an ef they was tuk’d awa wone nite, theys shur to be hal rite up top o’ the hil fust thing in morenin” (Hunt 1881, 176).

The following is from the Cornish Telegraph of Sept. 4th, 1861: “Zennor Quoit, one of our local antiquities, has recently had a narrow escape… A farmer had removed a part of one of the upright pillars, and drilled a hole into the slanting quoit, in order to erect a cattle-shed, when news of the vandalism reached the ears of the Rev. W. Borlase, vicar of Zennor, and for five shillings the work of destruction was stayed, the vicar having thus strengthened the legend that the quoit cannot be removed”‘.

In 1872 William Copeland Borlase records Chun Quoit in his book, ‘Naenia Cornubiae’:

“Zennor Cromlech.

Zennor Quoit, as the Cromlech in the parish of that name is usually called, was, when Borlase wrote his History, the most interesting and prefect specimen of a Kist-Vaen in Western Cornwall. In all probability it had been freshly disinterred from its cairn, or rather the gigantic structure had just succeeded in shaking off, or piercing up through, the crust of loose debris which had been piled over it ; for in the middle of the last century, “a stone barrow, fourteen yards in diameter, was heaped round it, and almost reached to the edge of the Quoit”. *(The word Quoit is here used for the cap-stone only).* Care had been taken, however, in its erection, that no stone should get into the chamber, and it was with great difficulty that a man could squeeze himself into it. Since then, progress and destruction, working together as usual, have much impaired the monument ; the cap-stone has been rolled off, and the other stones otherwise damaged by being made to serve as the supports of a cart-shed. Fortunately an original drawing and a plan were made for Dr. Borlase’s work, and these the author has been able to reproduce in woodcut from copies of the identical copper-plates then used. They will be found much more accurate and valuable than any ketch of the ruin, as it is at present, could possibly be.

The accounts which accompanies these engravings is as follows:-“On the top of a high hill about half a mile to the east of Senar Church-town stands a very large handsome Cromleh ; the area inclosed by the supporters is six feet eight inches by four feet, and points east and west. The Kist-Vaen is neatly formed, and fenced every way, and the (Eastern) supporter is 8 feet 10 inches high, from the surface of the earth in the Kist-Vaen, to the under face of the Quoit.

.The side stones of the Kist-Vaen, running on beyond the end stone, form a little cell to the east, by means of two stones terminating them at right angles. The great depth of this Kist-Vaen, which is about eight feet, at a medium under the plane of the Quoit, is remarkable. The Quoit was brought from a karn about a furlong off, which stands a little higher than the spot on which this Cromleh is erected.

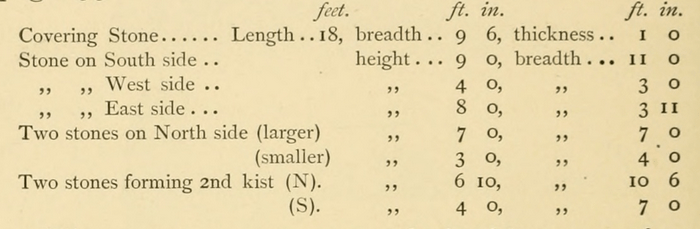

The following measurements of the stones which compose this Cromleh were taken on the 17th of February, 1872, and very closely accord with those obtained by the scale which accompanies the plan at page 53.-

…The apparent attempt made in this case to form a second Kist-Vaen is very remarkable. If it really be such, it is a unique instance in Cornwall of what is very commonly found in other Cromlech-bearing countries. It reminds us of those of Northern and Western Wales, and of Anglesea especially, where a small Kist-Vaen, side by side with the larger one, seems to be the rule and not the exception. In all instances, however, that the author has observed, that in the latter district, the smaller Cromlech has its own appropriate covering stone, while at Zennor both were under one and the same roof. At Loch Maria Ker, in Brittany, and elsewhere in the same country, there seem to be examples much more in point. M. Fremenville observes in reference to once of them- “Ons’apercoit que l’interirur etait partage an deux chambres par une cloison composee de deux pierres plantees sur champ. Ces seperations se remarquent dans beaucoup d’autres dolmens; plusieurs meme sout divises en trois chambres.” A drawing of the Cromlech at Loch Maria Ker will be found in Col. Forbes Leslie’s Early Races of Scotland, Vol ii, page 281.

It may be noticed that there are remains of ancient hut dwellings at Carne, about a furlong east of the Zennor Cromlech.” – https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t9r213s92&seq=73&q1=zennor

Excavations at Zennor Quoit:

Charles Thomas and Bernard Wailes reviewed the excavation history and the finds from Zennor Quoit in their report on the 1954 excavation of Sperris Quoit, about 1/4 mile away in Tregerthen tenement (Thomas and Wailes 1967). The following is a summary of the relevant portions of their report. A pot was discovered by a local man ‘some time in the 19th century’ while digging in the Quoit; the pot was apparently smashed (Thomas and Wailes 1967, 15). In 1881 another local man, called Grenfell visited the site and ‘finding that other people were searching about, he and his son thought they would have ‘a bit of a speer too’ After removing some of the earth, they came upon a flat stone, which they ‘shut’ (blasted). Then they removed more earth, and came upon another flat stone, which they also ‘shut’. Underneath that he found…an ancient whetstone’ (Thomas and Wailes 1967, 15, citing the report of the annual excursion of the PZNHAS of 1882). This was, in fact, a performated hone (Herring 1987A Fig. 6); Grenfell gave it to a Professor Westlake (living at Eagle’s Nest) who passed it on to W C Borlase the local antiquarian who presented it to the Society’s museum in Penzance (ie Penlee House Museum).

In October 1910 Mr R J Noall of St Ives dug within the main chamber and found, in its floor, eighteen flints (one a scraper, another calcined) (see Herring 1987A Fig. 6), some charcoal, some cremated bones, and most usefully, sherds from two small pots (see ibid Fig.6). Some of the sherds are now in the museum of the Royal Institution of Cornwall in Truro (the county museum), others now lost were fortunately drawn by Florence Patchett (1944, Herring 1987A Fig. 2). Just after the First World War a Mr Hazzeldine Warren found sherds of cord-impressed ware thrown up by rabbits immediately outside the entrance to the antechamber (Thomas and Wailes 1967, 16).

The cremated bones Mr Noall found were in a ‘little hollow in the floor’ of the chamber, at its eastern end. Thomas and Wailes regard this as a ‘token cremation’ and suggest the small pots and the flints were associated with it (1967, 16). They also argue that the Grenfells dug in the antechamber and found the hone here and suggest that Mr Warren’s cord-impressed ware came from the antechamber too (ibid, 17). It was suggested by Thomas and Wailes that the ‘original rite’ in the West Penwith chambered tombs involved token cremations associated with pits (1967, 20). The evidence for this is scanty as all the surviving tombs have been tampered with in antiquity, but it does seem that burials as such were not of very great importance at these monuments. This theme is taken up by Barnatt who suggests they served several functions: territorial markers (based perhaps on the tombs being symbolic ancestral resting places); places for rituals involving the living rather than the dead (eg based on astronomical occurrences, or seasons; places to satisfy secular needs (exchange of goods; wife-finding; settling disputes etc) (Barnatt 1982, 37-41).

The date of the chambered tombs is also uncertain. In their review of Sperris and Zennor Quoits, Thomas and Wailes conclude that the Cornish tombs were probably relatively late. The small globular pots found with the cremation at Zennor may be late Neolithic or even Early Bronze Age and the cord-impressed and performated hone from a secondary (?) deposit in the antechamber are Early/Middle Bronze Age; it is argued that these would most likely have been deposited while the monument retained its meaning for the community and might again suggest a fairly late date (Thomas and Wailes 1967, 20-22). We still await the excavation of a Cornish chambered tomb sufficiently well-preserved to contain material useful for dating and interpreting these monuments. Recent work in Wales suggests that rather than being Later Neolithic, the simple chambered tombs like Zennor may be among the earliest monuments in Britain and could date to the Early Neolithic, the fourth millennium (see Barnatt 1982, 43-5). – https://hsds.ac.uk/data-catalogue/resource/7a559e6864c01002b6dd82290450e2518219c029f6d00ac32d225e7af0c38ca6

Leave a comment