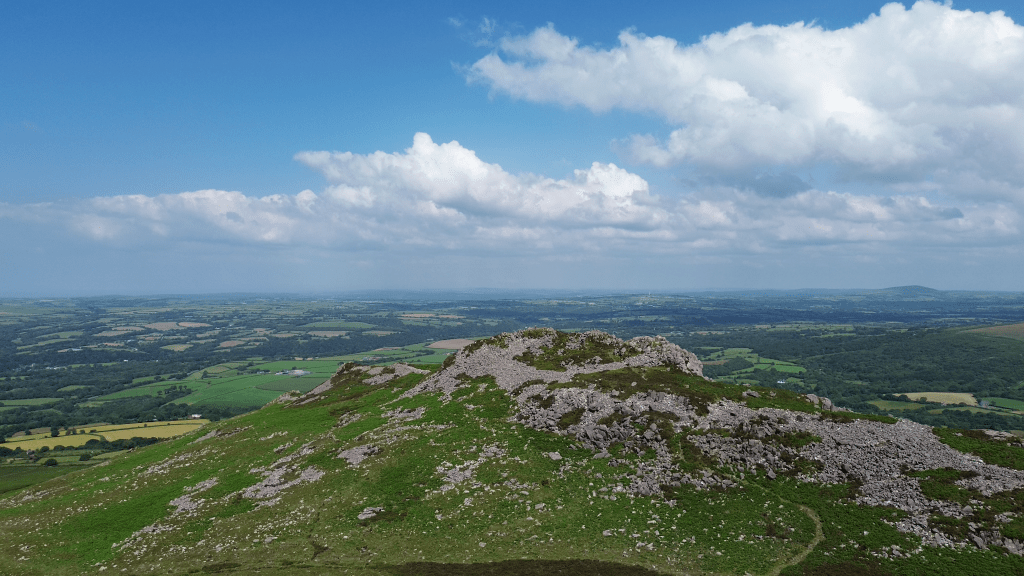

Mynydd Carningli is in the Preseli Hills of Pembrokeshire, Wales. This is an ancient volcano with a striking silhouette dominating the surrounding landscape. At the summit sits a vast Iron Age hillfort.. Amongst the lower slopes are scattered remains of Bronze Age occupation. Some features of the mountain may even go as far back as the neolithic period.

CADW description of Carn Ingli:

“The first detailed archaeological survey of the multitude of stone enclosures was published by A H A Hogg in 1973, who was able to establish many aspects about the site which make it unusual in Welsh prehistory. The natural summit crags of Carn-ingli are enclosed by a long fortification formed of high, rough-built defensive walls. The earliest phases appear to be three conjoined enclosures on the highest point, which are probably the result of multiple periods of occupation and enlargement. The fourth and largest enclosure extends to the north onto lower ground and is crowded with stone-built huts and pounds and even the remains of an old street or track. In all, the ramparts are pierced by twelve gateways, some through the cross walls which divide the successive enclosures, and some through the main outer walls. This is a very high number of vulnerable openings to defend if we assume the structure is an Iron Age hillfort, and it may be that parts of Carn-ingli date back far earlier, to the Neolithic or Bronze Age. Another remarkable feature about the hilltop is the number of small pounds and platforms built on the slopes surrounding the fort, thought by Hogg to have been designed in prehistory to cultivate crops in the thin, stony soils.

Some researchers have suggested that parts of Carn-ingli were occupied during the early medieval period, but Hogg cited the widespread, apparently deliberate, throwing down of walls and ramparts across the hillfort as evidence for systematic destruction by Roman invaders in the aftermath of the conquest of Wales. Such a dramatic interpretation, placing the Roman legions on the slopes of Carn-ingli in an attack on its inhabitants, might be questioned today.

All around Carn-ingli hillfort, particularly on the lower hillslopes to the north and west, survives a rich and well-preserved landscape of old field boundaries, clearance cairns, round huts and farmsteads which represents one of the great surviving prehistoric landscapes of southern Britain, . Uunploughed in recent centuries., but enclosed and improved along its northern fringes by historic fields radiating from Newport and Dinas Cross, aAerial photography is a particularly powerful way to show the dense surviving remains of a prehistoric hillside as it was farmed and settled, probably dating to the Bronze and Iron Ages. Doctoral research by Alastair Pearson of the University of Portsmouth in the 1980s and 1990s suggested that many of these fields and worn trackways had their origins in the Bronze Age. T. Driver, RCAHMW, 18 December 2009.”

The earliest record of Mynydd Carn Ingli is from the 12th century.. Naming it Mons Angleorum – The Mountain of Angels. According to legend, this is where St. Brynach, a wandering saint from the 6th century, would retreat to pray. Here, amongst the windswept rocks, he was said to meet and converse with angels, or divine messengers.

The legend is also mentioned in ‘A Historical Tour Through Pembrokeshire’, published in 1810. Antiquarian Richard Fenton recalls:

“..St. Byrnach, who flourished in the sixth century, and was a contemporary of St. David. He is reputed to have lived an eremitical life in the neighbourhood of a certain mountain of Cemaes, where legend says he was often visited by angels, who spiritually ministered to him, and that the place was thence denominated “Mons Angelorum”, which could be no other than that which is now called Carn Engylion, or, as it is corrupted, Carn Englyn.”

The form of the mountain itself fuels speculation. Many believe that the silhouette of the mountain resembles the reclining figure of a woman – swollen as if with child. Is she a sleeping goddess? This mountain her resting place.. echoing ancient tradition that linked features of the landscape to the divine feminine.

Is it a sleeping giant? George Owen of Henllys (1552–1613), says: “The next mountaine of note and bignes, is the high sharpe rocke over Newport, called Carn Englyn, supposed by the vulgar to take its appellative from a Cawr of giant of that name, is a very steepe and stony mountaine, having the toppe thereof sharpe, and all rockes shewing from the east and by north like the uuper part of the cappital Greek omega.”

Brian John describes the mountain on his website:

“The little mountain of Carningli dominates the landscape around Newport and Cilgwyn, and although it is only 347m ( 1,138 feet) high it is visible as a prominent feature from the north and east, and even from the south, for travellers approaching from Mynydd Preseli. From certain directions, the mountain looks like a volcanic peak — and this is appropriate, since it is indeed an ancient volcano. But it is extremely ancient — around 450 million years old, be be almost precise — and its present-day profile gives us little guidance as to what it looked like when it was erupting. When the mountain was born, the area which we currently call North Pembrokeshire was part of a great ocean, the bed of which was buckled up and down and shattered by earth movements and mountain building over millions of years. There was virtually no life on land, and very little in the sea. We know that there were tens if not hundreds of volcanoes across a wide area, since dolerites and other volcanic rocks occur in virtually all of the high points of the landscape.

Carningli probably started to emerge from the sea as a violent volcanic island, appearing, erupting and growing just as the Icelandic island of Surtsey did in 1963. Ash and lava from the eruption must be present over a wide area beneath the present-day land surface, interbedded with old sea-floor sediments of sand, silt and clay which have now been transformed into solid rock. The only place where we can see the volcanic ash today is in the cliffs between Newport and Cwm-yr-Eglwys, in great beds of crumbly grey material which looks very different from the dark-coloured and flaky shale which the locals call “rab.”

When the Carningli eruption came to an end, the volcanic island immediately started to be whittled away by wave action, wind and running water. The land surface, originally many thousands of feet above its present position, was lowered inexorably by erosion, so that what we see today is essentially the “core” of the original mountain, made largely of a very hard blue-grey rock called dolerite. Some of it is “spotted dolerite” like the famous bluestone of Carn Meini.

During the Ice Age the mountain was completely covered by the ice of the massive Irish Sea Glacier, moving down from the north and north-west, possibly in several different glacial episodes. Some traces of ice erosion can still be seen on rocky slabs near the summit and on the eastern flank of the mountain. In the last glacial episode the glacier may not have over-ridden the summit, but it pressed against the northern slopes and probably into the amphitheatre of Cilgwyn, leaving the southern and eastern slopes to be afflicted by thousands of years of frost shattering. That is why the east face of Carningli is almost obliterated by a great bank of scree even today. Martha and her children loved to climb on the great jumble of boulders and craggy outcrops, and somewhere, in the middle of it all, is Martha’s cave and the crevice into which she dumped Moses Lloyd’s body.

The summit of the mountain is protected in part by a splendid defensive embankment, now somewhat ruinous but still obvious to all who climb up from the north or west. In its heyday it was probably about 10 feet high, with a vertical outward face, and maybe even a timber palisade on top. When you climb up from the east (for example, from the car-park on the Dolrannog Road) the embankment is not so obvious; that is because the scree slopes provided good natural defences for the inhabitants of the mountain against marauding warriors. So the embankment never did enclose the whole of the summit. There was a fortified village here, aligned more or less SW-NE, with three segments. The builders knew all about military architecture, and in some ways it was just as sophisticated as that of the Normans who followed maybe 2,000 years later.” – https://www.brianjohn.co.uk/carningli.html

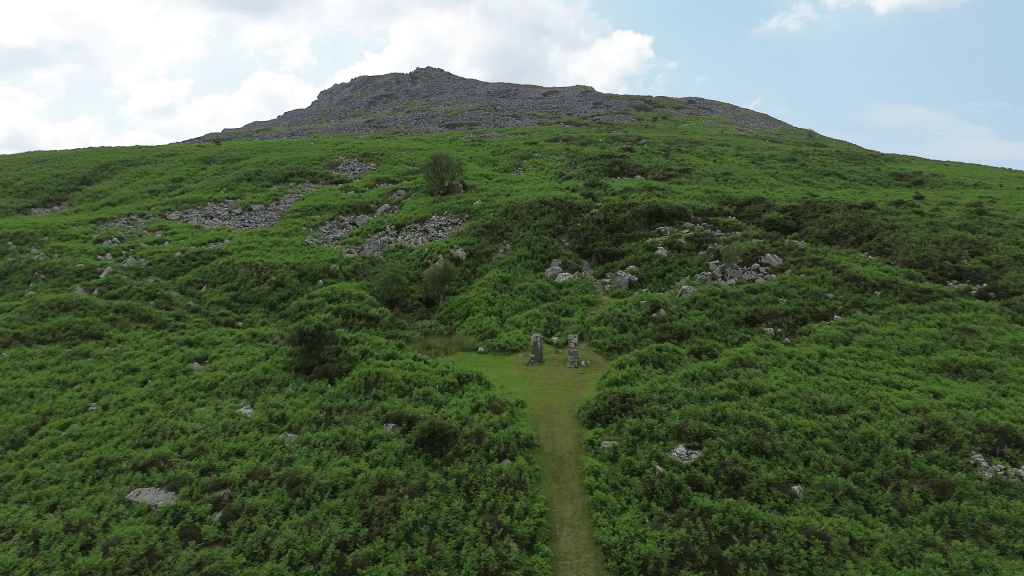

There was once a little “mountain railway” on Carningli, carrying broken stone from a small quarry down to a crushing plant on the Cilgwyn Road. Some railway sleepers can still be found in the turf, but otherwise the only traces remaining are the two stone pillars that supported a cable drum — a cable was used to control the descent of the loaded wagons as they rolled downhill, and then to pull the empty ones back up again. This little industry was abandoned before 1930.

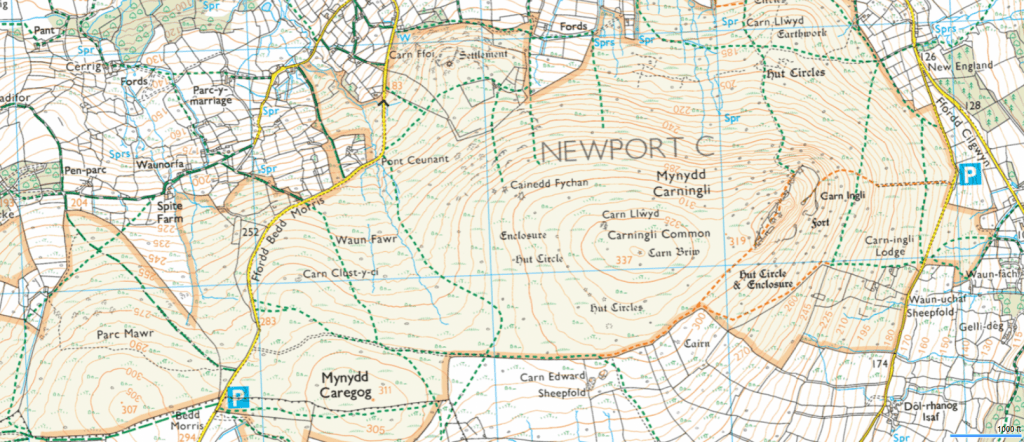

Walking Carningli:

We like to start at one of the 2 parking spots shown on the map below.

Leave a comment